6.3. DYNAMIC FORCE ANALYSIS:

6.3.1. Center of Mass and Moment of Inertia of a Rigid Body

Newton’s second law of motion as stated can be applied directly if the body considered is of negligible dimensions. Such bodies we call a particle. Rigid bodies of finite dimensions can be considered to be composed of a system of particles. For the rigid bodies we must define the center of mass and the moment of inertia.

Center of mass, G, is commonly known as the center of gravity, and is defined as a point on the rigid body whose position is given by:

\displaystyle \vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}=\frac{\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}}{\text{m}}

where \displaystyle {\text{m}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}, total mass of the rigid body. In Cartesian coordinates:

\displaystyle {\text{x}}_{\text{G}}=\frac{\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}}{\text{m}} and \displaystyle {\text{y}}_{\text{G}}=\frac{\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}}{\text{m}}

Moment of inertia gives us the mass distribution within the rigid body. For rigid bodies in a plane the moment of inertia with respect to an axis normal to the plane and passing through O is defined by:

\displaystyle {\text{I}}_{\text{0}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left({{{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}}^2+{{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}}^2}\right){\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}}^2{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}

and by definition:

\displaystyle {\text{k}}_{\text{0}}=\sqrt{\frac{ {\text{I}}_{\text{0}}}{{\text{m}}}}

where k0 is known as the radius of gyration of the rigid body with respect to an axis passing through O. The moment of inertia of the rigid body with respect to the center of gravity is given by:

\displaystyle {\text{I}}_{\text{G}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left({{{\text{u}}_{\text{i}}}^2+{{\text{v}}_{\text{i}}}^2}\right){\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}

We can write I0 as:

\displaystyle {\text{I}}_{\text{0}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left({{{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}}^2+{{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}}^2}\right){\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left[{{\left({\text{x}}_{\text{G}}+{\text{u}}_{\text{i}}\right)}^2+{\left({\text{y}}_{\text{G}}+{\text{v}}_{\text{i}}\right)}^2}\right]{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}

Since ui and vi are the coordinates of the particle with respect to the center of gravity, \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{u}}_{\text{i}}{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{v}}_{\text{i}}{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}=0. Therefore:

\displaystyle {\text{I}}_{\text{O}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left({{{\text{u}}_{\text{i}}}^2+{{\text{v}}_{\text{i}}}^2}\right){\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}+\left({{{\text{x}}_{\text{G}}}^2+{{\text{y}}_{\text{G}}}^2}\right)\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}}={\text{I}}_{\text{G}}+{{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}}^2{\text{m}}=\left({{{\text{k}}_{\text{G}}}^2+{{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}}^2}\right){\text{m}}

where kG is the radius of gyration about the center of gravity and rG is the magnitude of the position vector of the center of gravity from O. We thus have a fundamental theorem.

6.3.2. Parallel Axis Theorem

The moment of inertia of a body about any axis is equal to the moment of inertia about a parallel axis passing through the center of gravity plus the product of the mass of the rigid body and the square of the distance between the two axes.

In the following table moments of inertia of some simple bodies are shown. For bodies of a complex shape the moments of inertia can be computed by separating the rigid body into some simple shapes and applying parallel axis theorem. Usually, if a drawing package with a solid model is used, the mass and the moments of inertia of the parts can be determined automatically by these packages. In general, the actual manufactured pieces may differ from the drawings in terms of the mass and the moment of inertia. In cases where the moment of inertia of an existing part is required, experimental methods are used to determine these quantities.

6.3.3. Newton’s Second Law of Motion for a Rigid Body

According to Newton’s second law the rate of change of momentum of a particle is proportional to the resultant external force acting on the particle. For a particle in the rigid body of constant mass mi, Newton’s second law becomes:

| \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}+\sum\limits_{\text{j}}{\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}}={\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i}}=\frac{{\text{d}}^2\left({\text{m}}_{\text{i}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}}\right)}{\text{d}{\text{t}}^2} | (1) |

where \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}_{\text{i}} is the external force acting on particle i and \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}is the force acting on particle i due to particle j. \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}} is commonly known as the internal force. If we consider all the particles within the rigid body:

| \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}}+ \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\sum\limits_{\text{j}}{\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}}}= \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i}}}=\frac{{\text{d}}^2 \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left({\text{m}}_{\text{i}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}}\right)}}{\text{d}{\text{t}}^2} | (2) |

Noting that \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}}=\sum{\vec{\text{F}}} = the sum of all the external forces acting on the rigid body, \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\sum\limits_{\text{j}}{\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}}}=\vec{\text{0}} since \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}+\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ij}}=\vec{\text{0}} due to Newton’s third law, and \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left({\text{m}}_{\text{i}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}}\right)}={\text{m}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}. We thus have Newton’s Second Law of Motion for Linear Momentum for a rigid body:

| \displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{F}}}=\frac{{\text{d}}^2\left({\text{m}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}}\right)}{\text{d}{\text{t}}^2}=\frac{{\text{d}}\left({\text{m}}{\vec{\text{v}}_{\text{G}}}\right)}{\text{dt}}={\text{m}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{G}} | (I) |

From this equation one can see that the internal forces have no effect on the motion of the rigid body, the center of gravity behaves as if the whole mass is concentrated and the resultant force \displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{F}}} is acting upon this point. The term {\text{m}}{\vec{\text{v}}_{\text{G}}} is the linear momentum of the rigid body. If we take the moment of the forces in equation (1) with respect to point O, we obtain:

| \displaystyle \vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}+\sum\limits_{\text{j}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}}={\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i}} | (3) |

The acceleration of point i, \displaystyle \vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i}}, can be written in terms of the acceleration of point 0 and relative accelerations as:

\displaystyle \vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i}}=\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}}+\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i/O}}=\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}}+{\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i/O}}}^{\text{t}}+{\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i/O}}}^{\text{n}}

where \displaystyle {\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i/O}}}^{\text{t}} and \displaystyle {\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i/O}}}^{\text{n}} are the relative tangential and normal accelerations of point i with respect to point O. In vector notation these terms are given by:

\displaystyle {\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i/O}}}^{\text{t}}=\vec{\text{α}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}} and \displaystyle {\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i/O}}}^{\text{n}}=-{\text{ω}}^2\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}

where α and ω are the angular acceleration and speed of the rigid body respectively. Substituting the above relations into equation (3) and summing up for all particles within the rigid body results in:

| \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}}+ \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\sum\limits_{\text{j}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{i}}}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left[{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\left(\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}}+\vec{\text{α}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}-{\text{ω}}^2\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}\right)\right]} | (4) |

Noting that \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}}=\sum{\vec{\text{M}}_{\text{O}}} = sum of the moments acting along an axis passing through O (perpendicular to the plane) and \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\sum\limits_{\text{j}}{\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}}}=\vec{\text{0}} (since \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ji}}=-\vec{\text{F}}_{\text{ij}} and these forces have same line of action). The terms on the right hand side of equation (4) can be written as:

| \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{\left[{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\left(\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{o}}+\vec{\text{α}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}-{\text{ω}}^2\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}\right)\right]}=\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}}}+\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\left(\vec{\text{α}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}\right)}-{\text{ω}}^2\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}} | (5) |

Now, \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{o}}}={\text{m}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}}, \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\left(\vec{\text{α}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}\right)}=\vec{\text{α}}\sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}{{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}}^2}={\text{I}}_{\text{O}}\vec{\text{α}} and \displaystyle \sum\limits_{\text{i}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{i}}}=\vec{\text{0}}. Hence, equation (4) simplifies into:

| \displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{M}}_{\text{O}}}={\text{m}}\vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}}+{\text{I}}_{\text{O}}\vec{\text{α}} | (6) |

In general \displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{M}}_{\text{O}}}\neq{\text{I}}_{\text{O}}\vec{\text{α}}. The first term on the right-hand side of equation (6) will vanish if \displaystyle \vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}}=\vec{\text{0}} or \displaystyle \vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}=\vec{\text{0}} or if \displaystyle \vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}} and \displaystyle \vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}} are parallel. The acceleration of point O is zero if point O is the acceleration pole or if the rigid body is in a rotation about point O.

\displaystyle \vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}=\vec{\text{0}} means that point O coincides with the center of gravity G and \displaystyle \vec{\text{a}}_{\text{O}}=\vec{\text{0}} will be parallel to \displaystyle \vec{\text{r}}_{\text{G}}=\vec{\text{0}} only in very special cases. However in any general case the center of gravity can be made coincident with the center of the reference axis. We thus have Newton’s Second Law of Motion for Angular Momentum of a rigid body, which is:

| \displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{M}}_{\text{G}}}=\frac{{\text{d}}^2\left({\text{I}}_{\text{G}}{\vec{\text{θ}}}\right)}{\text{d}{\text{t}}^2}=\frac{{\text{d}}\left({\text{I}}_{\text{G}}{\vec{\text{ω}}}\right)}{\text{dt}}={\text{I}}_{\text{G}}\vec{\text{α}} | (II) |

Note that both the moment of external forces and the moment of inertia of the rigid body must be with respect to an axis passing through the center of gravity and perpendicular to the plane of motion. The term \displaystyle {\text{I}}_{\text{G}}\vec{\text{ω}} is the angular momentum of the rigid body about the center of gravity.

6.3.4. D’Alambert’s Principle

Equations I and II can be written in the following form:

| \displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{F}}}-{\text{m}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{G}}=\vec{\text{0}} | (I) |

and

| \displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{M}}_{\text{G}}}-{\text{I}}_{\text{G}}\vec{\text{α}}=\vec{\text{0}} | (II) |

Now the term -{\text{m}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{G}} has the magnitude of a force. Equation (I) is a vector equation which states that the vector sum of all the external forces plus the fictitious force of magnitude and direction -{\text{m}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{G}} are zero. The fictitious force -{\text{m}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{G}} is known as the inertia force which will be denoted by \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}^{\text{i}}:

\displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}^{\text{i}}=-{\text{m}}\vec{\text{a}}_{\text{G}}

\displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}^{\text{i}} has the same line of action of \vec{\text{a}}_{\text{G}} but it is in opposite direction.

Similarly, the term -{\text{I}}_{\text{G}}\vec{\text{α}} has the magnitude of a moment and Equation (II) is a vector equation which states that the vector sum of all the external moments about the center of gravity plus a fictitious moment of magnitude and direction -{\text{I}}_{\text{G}}\vec{\text{α}} are zero. This fictitious moment is known as the inertia moment and it will be denoted by \displaystyle \vec{\text{M}}^{\text{i}}:

\displaystyle \vec{\text{M}}^{\text{i}}= -{\text{I}}_{\text{G}}\vec{\text{α}}

\displaystyle \vec{\text{M}}^{\text{i}} is in opposite sense of the angular acceleration \displaystyle \vec{\text{α}}. Using inertia force and inertia moment, Newton’s Second Law of Motion for a rigid body results with the equations:

\displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{F}}}+ \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}^{\text{i}}=\vec{\text{0}}

and

\displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{M}}_{\text{G}}}+ \displaystyle \vec{\text{M}}^{\text{i}}=\vec{\text{0}}

We can as well treat the inertia terms as if they were another external force or moment acting on the rigid body, in which case:

\displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{F}}}=\vec{\text{0}}

and

\displaystyle \sum{\vec{\text{M}}_{\text{G}}}=\vec{\text{0}}

where the summation includes both the external and inertia forces and moments. This concept is known as D'Alambert's Principle which can be stated as follows:

D'Alambert's Principle

In a body moving with known angular acceleration and linear acceleration of the center of gravity, the vector sum of all the external forces and inertia forces and the vector sum of all the external moments and inertia moment are both separately equal to zero.

D'Alambert's principle is very useful in the dynamic force analysis of machinery. In great many problems we know the acceleration characteristics of the members in the machine structure and we can determine the inertia forces and torques. These inertia forces and torques can be treated as if they are external forces and the procedure of static force analysis can be carried out for this dynamic case. However one must never think the inertia forces and moments as real forces. They are fictitious forces and they never exist. Acceleration is a result of the external forces.

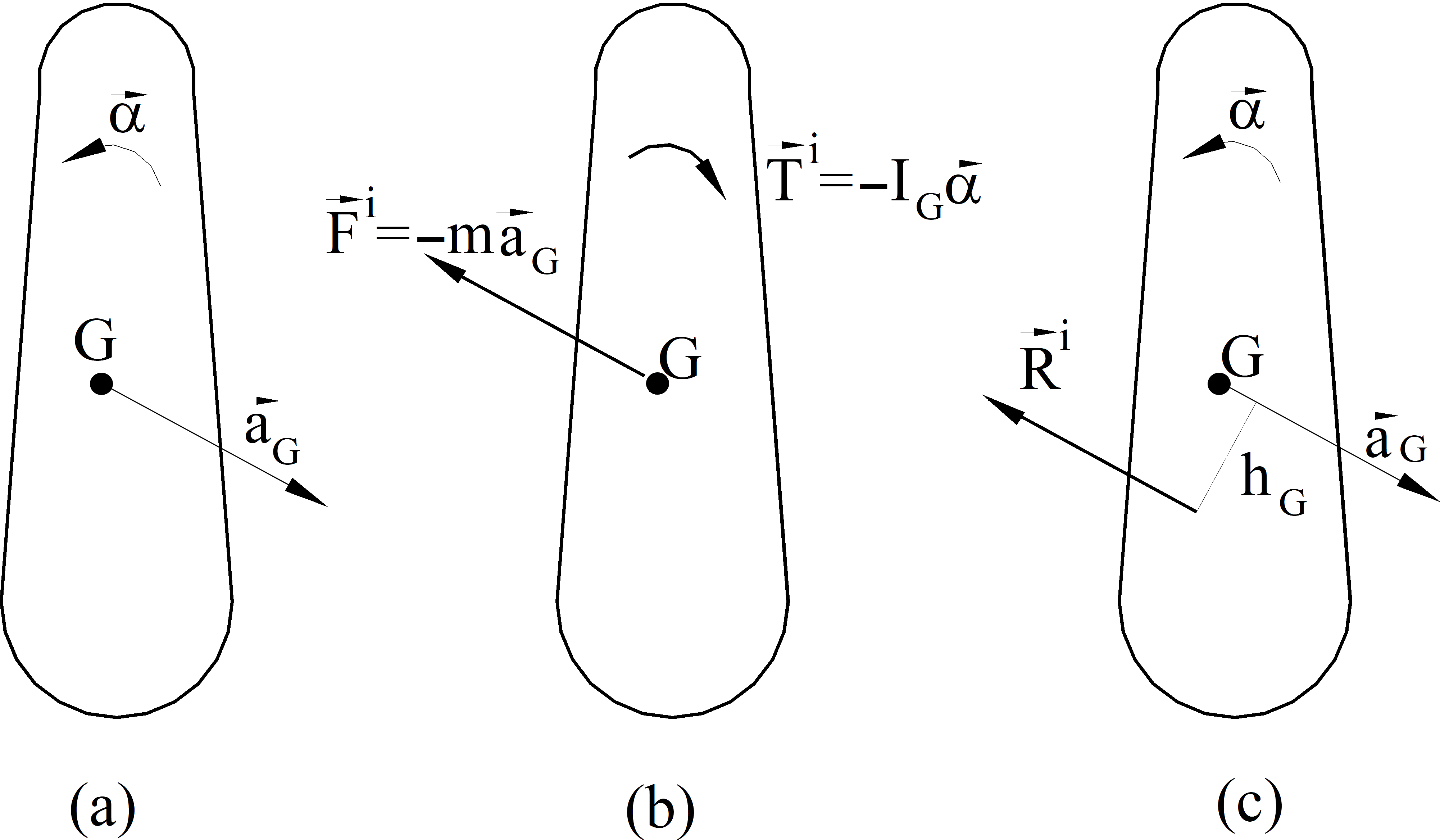

In graphical solutions it is convenient to replace the inertia force and torque by an equivalent resultant inertia force. Consider a rigid body with \vec{\text{a}}_{\text{G}} as the acceleration of its center of gravity and \vec{\text{α}} as its angular acceleration (Figure (a)). The inertia force and moment will be as shown in Figure (b). The inertia force and moment can be combined into a single resultant force \displaystyle \vec{\text{R}}^{\text{i}} (Figure (c)), if:

\displaystyle \vec{\text{R}}^{\text{i}}=\vec{\text{F}}^{\text{i}}

and

\displaystyle \vec{\text{r}}{\text{×}}\vec{\text{R}}^{\text{i}}= \vec{\text{M}}^{\text{i}}

where \displaystyle \vec{\text{r}} is a position vector from the center of gravity to a point on the line of action of \displaystyle \vec{\text{R}}^{\text{i}}. In such a case the resultant \displaystyle \vec{\text{R}}^{\text{i}} has the magnitude and direction of the inertia force \displaystyle \vec{\text{F}}^{\text{i}} and is displaced from the center of gravity by a perpendicular distance hG such that:

\displaystyle {\text{h}}_{\text{G}}=\frac{{\text{I}}_{\text{G}}{\text{α}}}{{\text{m}}{\text{a}}_{\text{G}}}=\frac{{{\text{k}}_{\text{G}}}^2{\text{α}}}{{\text{a}}_{\text{G}}}

This fictitious force \displaystyle \vec{\text{R}}^{\text{i}} will then replace the effect of the inertia force and torque