For the third homework of my CENG 795: Advanced Ray Tracing course, I expanded my ray tracer by implementing multisampling using stratified random sampling, depth of field, motion blur, and glossy reflections. I also fixed the broken features, like my BVH implementation, and added the missing ones: PLY parsing and mesh instances. I will be explaining my implementation process and the problems I encountered along the way in this blog post.

Fixing the BVH Structure and Adding the Missing Features

The features I failed to implement in my previous homework were absolutely necessary for this homework, so I had to go over my implementation yet again and hope that I’d be able to properly implement those features this time otherwise I wouldn’t even be able to start this homework.

For the BVH, I decided to redo it from scratch, but I didn’t really change its overall logic. The biggest change I made was removing the bottom layer BVH structures for meshes and instead treating the mesh faces as primitives themselves. A 2 level BVH structure probably would have been faster, but a BVH that actually works is much faster than one that doesn’t work at all. For the traversal, I used stacks for depth first traversal and kept the maximum primitive count per leaf to 4. This implementation seemed to have worked, but I could only check on simple scenes without PLY meshes, so I had to implement the PLY parsing before I could completely be sure that it worked.

After I managed to compile the PLY library without a million issues, I encountered yet another problem! Even though I didn’t get any compilation errors, now the reader function gave errors whenever it tried to read an element in the file. The only exception was dragon_remeshed_fixed.ply, for some reason it could only read the contents of this file. At least that meant that the parser was working, it just couldn’t read some files for some reason. Every time I tried to run it on another file, it gave out this error: “get_binary_item: bad type = 0”. Seeing that it had problems reading some binary items, I tried converting the files to ASCII encoding and reading them that way. Thankfully this worked. If it hadn’t, I have no idea what I would have done. With that out of the way implementing mesh instances was quite simple, I had implemented the BVH with mesh instances in consideration.

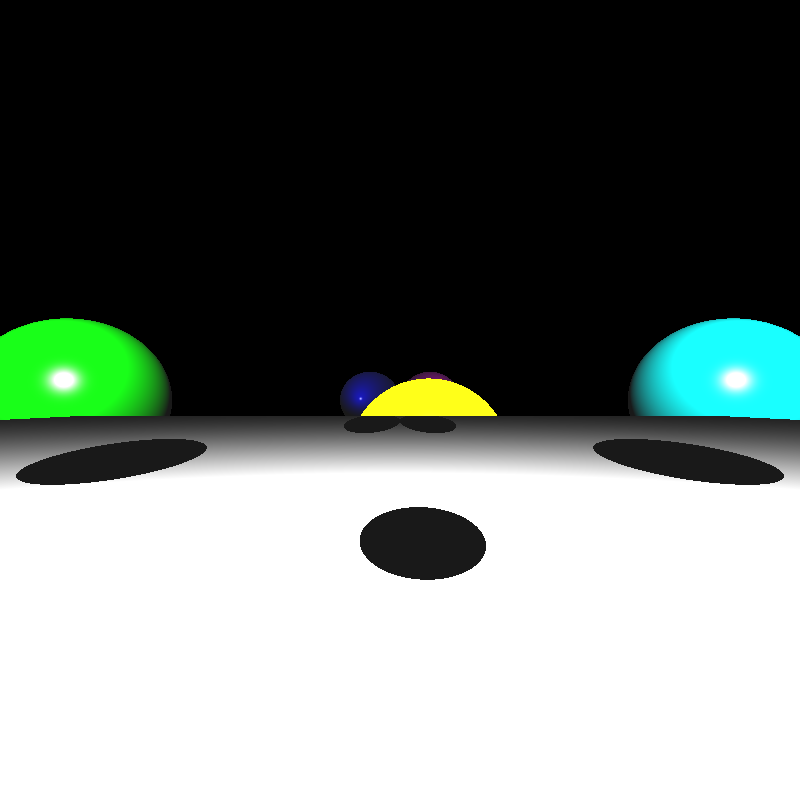

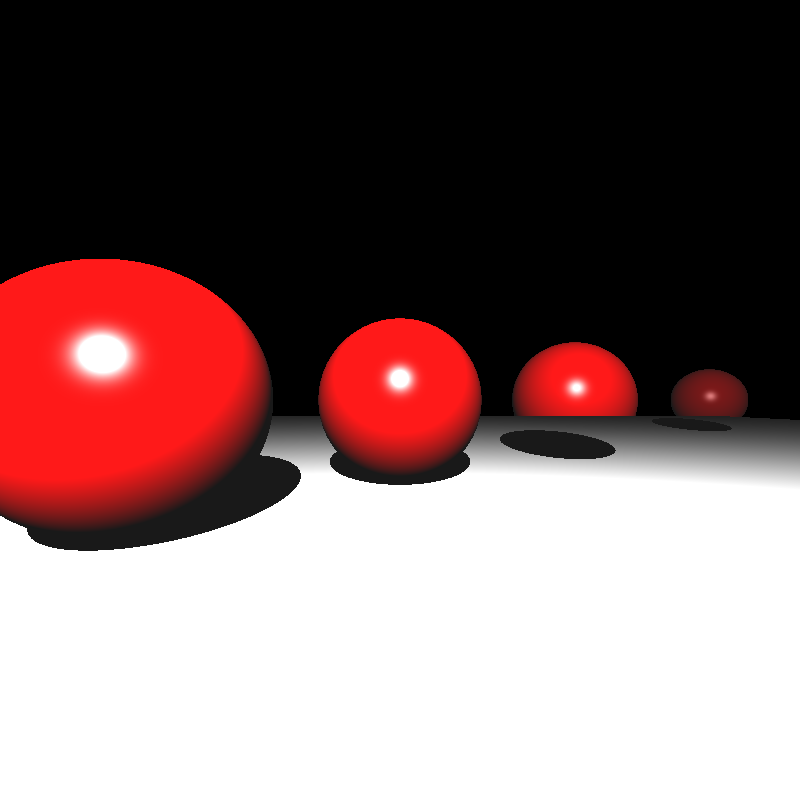

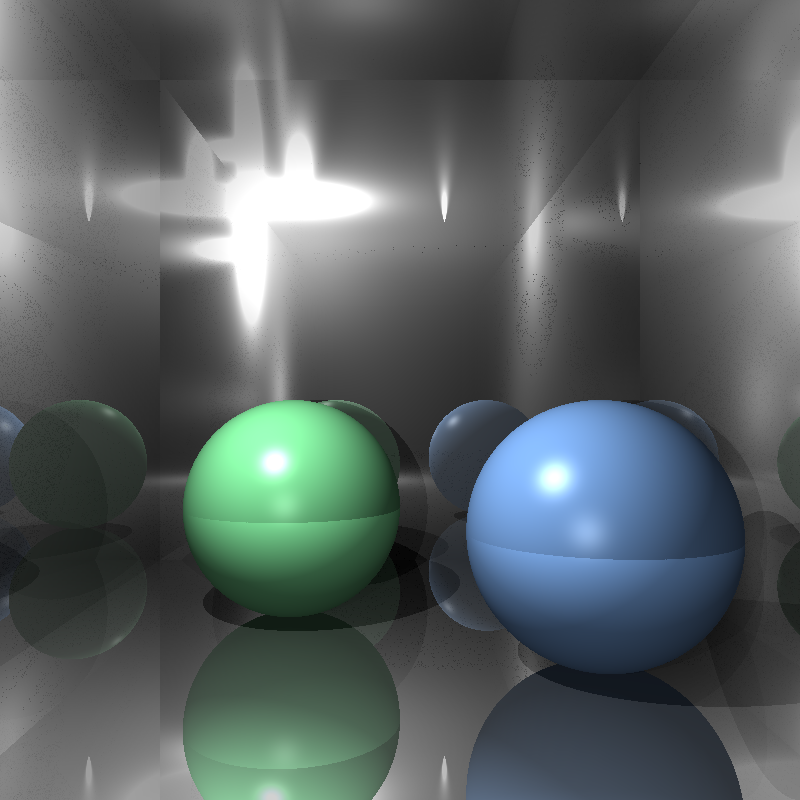

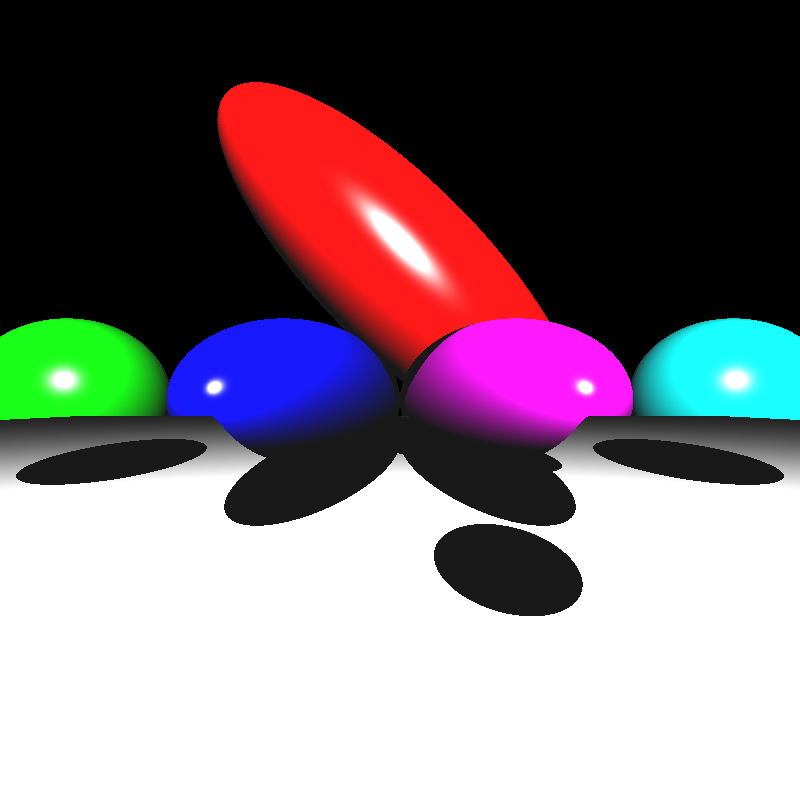

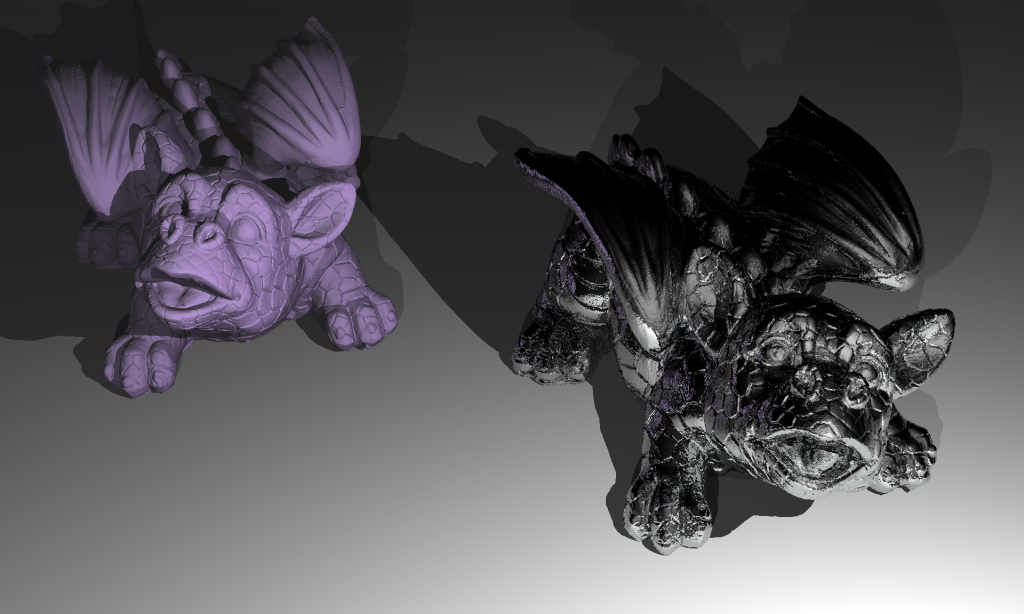

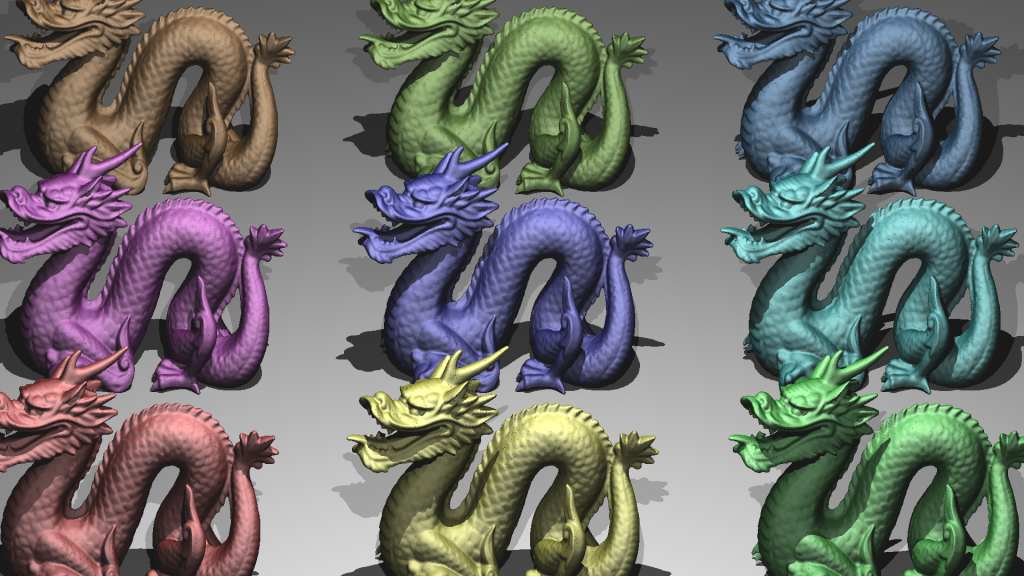

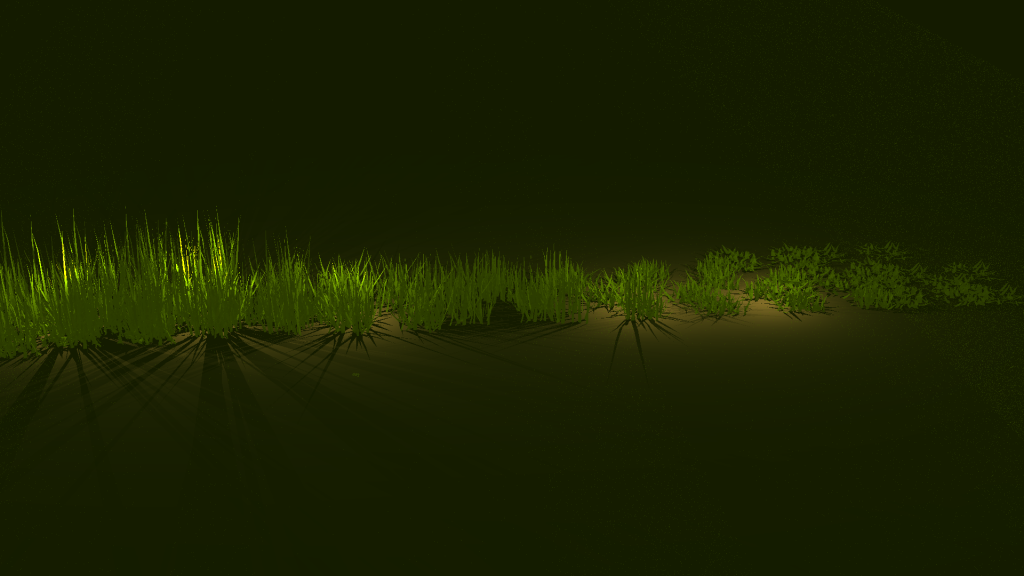

Now that all three features were implemented; I tested them, fixed some minor bugs I encountered, and finally I had a ray tracer that could read PLY files and had a working acceleration structure! Third time’s the charm I suppose. Below are the render times and the resulting images that were missing from my previous homework:

| Scene File | Render Time (seconds) |

| ellipsoids.json | 0.39 |

| spheres.json | 0.29 |

| mirror_room.json | 2.42 |

| metal_glass_plates.json | 7.65 |

| dragon_metal.json | 16.8 |

| marching_dragons.json | 6.29 |

| dragon_new_ply.json | 3.03 |

| grass_desert.json | 46.1 |

| two_berserkers.json | 0.5 |

Stratified Random Sampling and Area Light

Implementing stratified random sampling was quite straight forward. I used the given random sequence generator to generate random values, picked a random position for each sample in its tile, and traced normally for each sample. I also shuffled the sample indices for each pixel and applied Gaussian filtering to calculate the resulting color value. I didn’t encounter any errors during this process, but I didn’t find a noticable difference for the given scenes, perhaps because the scenes didn’t have much aliasing in the first place.

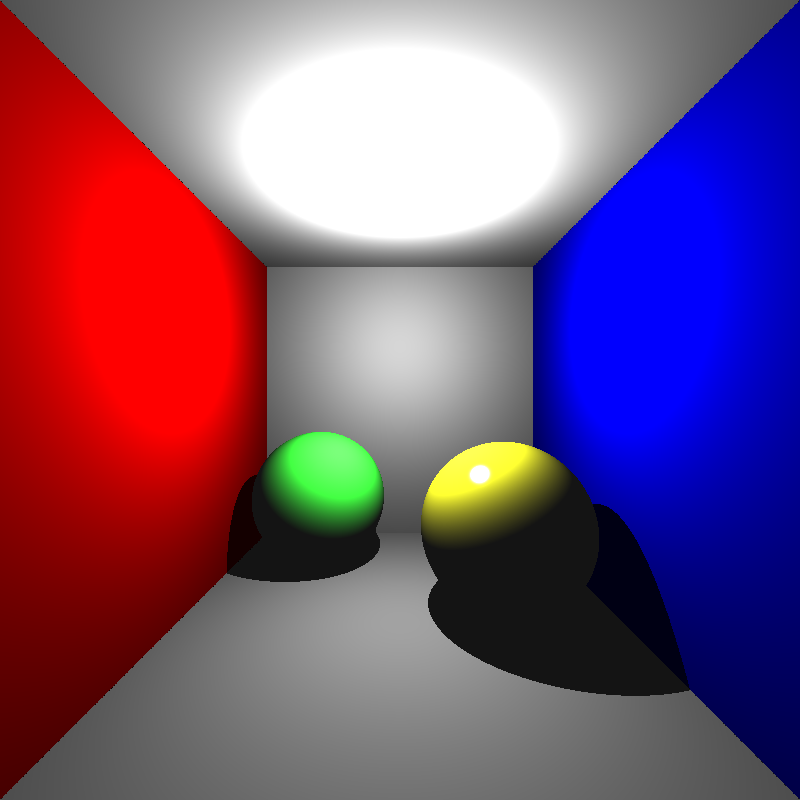

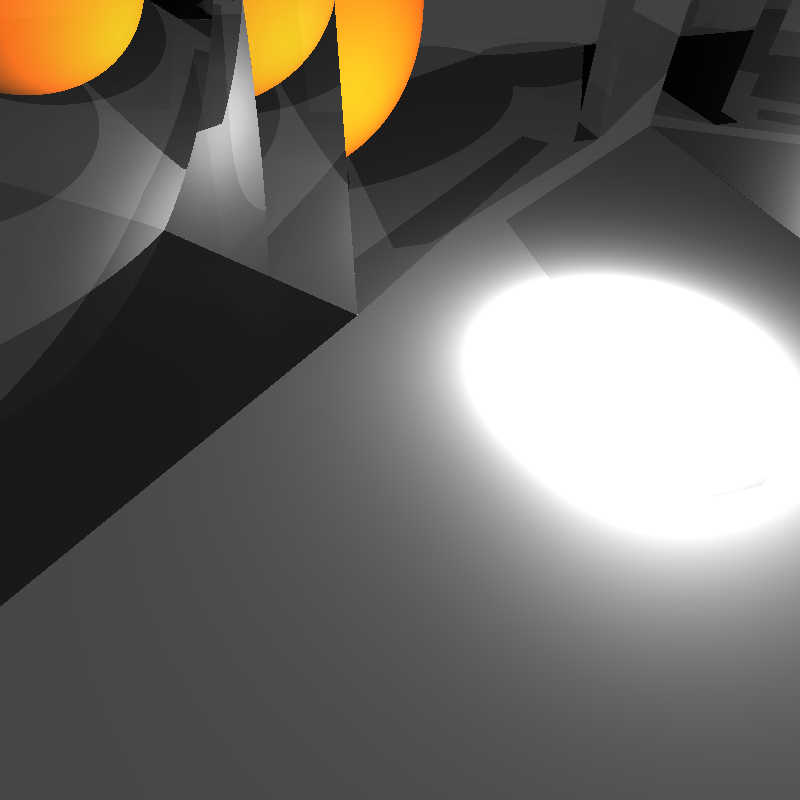

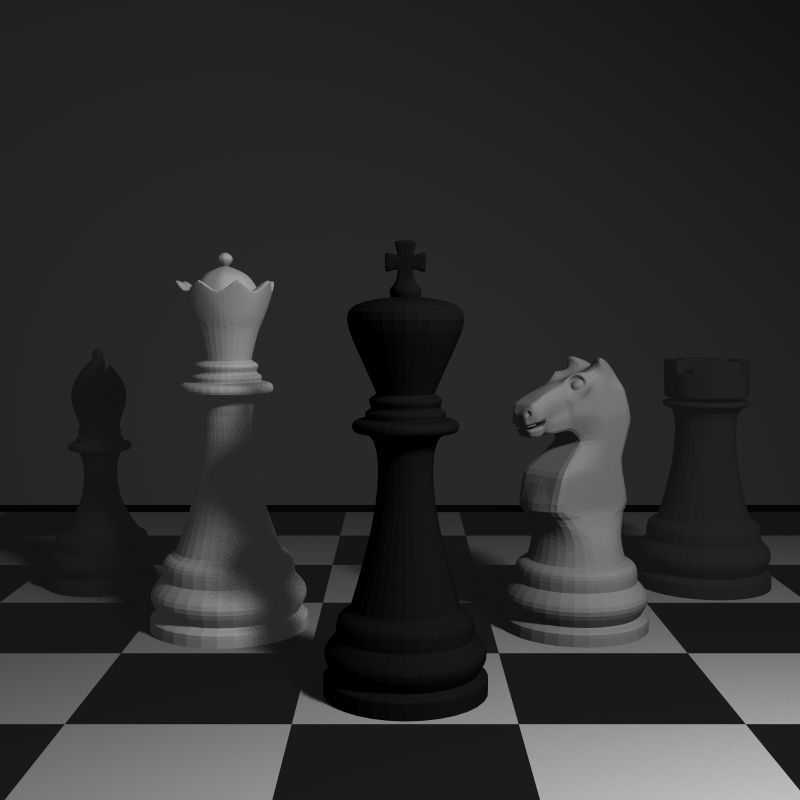

After that, I implemented area lights. I thought implementing area lights would be a simple process as well, but my initial results were quite odd. Below was my first rendering of cornellbox_area.json and chessboard_arealight.json after implementing area lights:

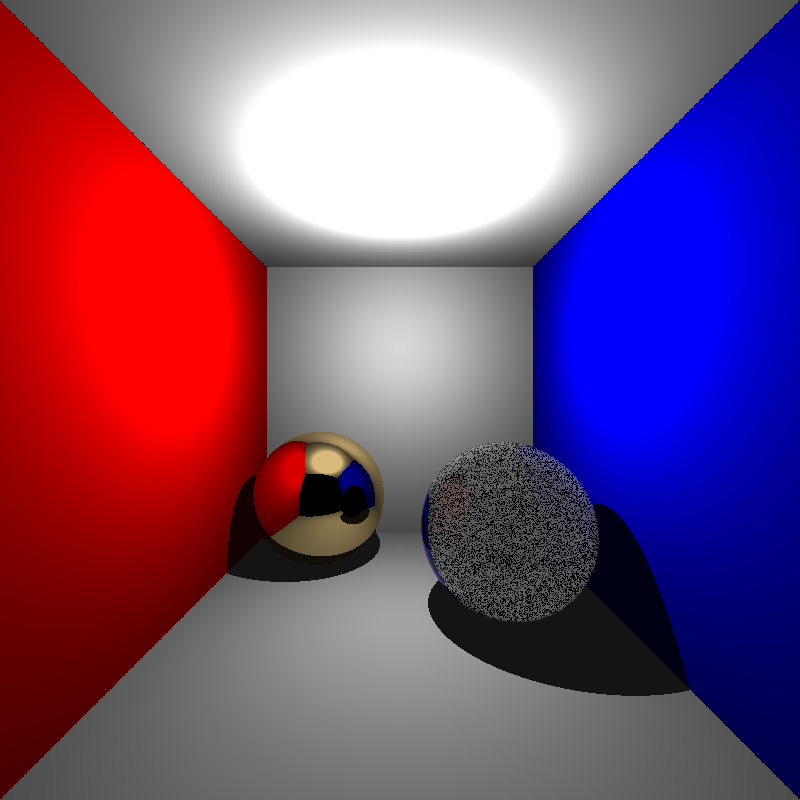

I thought the reason for this might be that I implemented the area lights as one directional. But even after modifying it to be two directional, the rendered images were still really dark. Then I checked if I was calculating the random positions correctly. After checking, I noticed I was adding the random values, which were between 0 and 1, without normalizing them so some of the random points I calculated on the area light were actually outside its area, but this shouldn’t have made the scene so dark. Sure enough, this was not the cause either. After doing a bit of testing, I found out the calculated directions and the shading values were really weird so I tried switching the ordering of the cross product when calculating the arbitrary normal. This worked yet it shouldn’t have, I was already considering the area light as two directional, so changing the ordering should not have made any difference. What was even weirder is that after switching the ordering back again, it still works! I’m still not sure what caused this, but I’ll figure it out another time. Below are the renderings of the two scenes above after my modifications:

Depth of Field

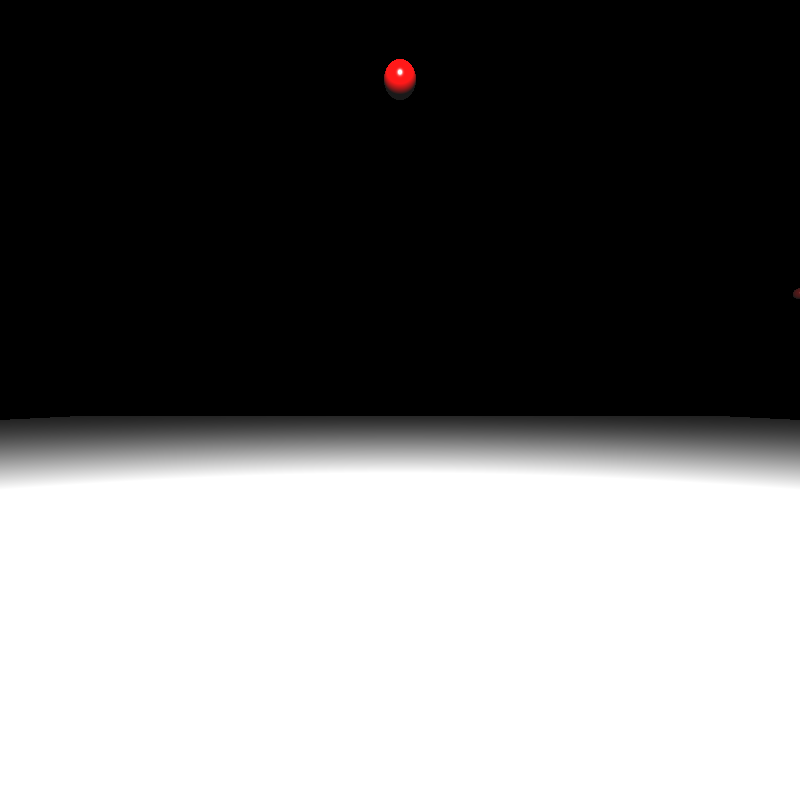

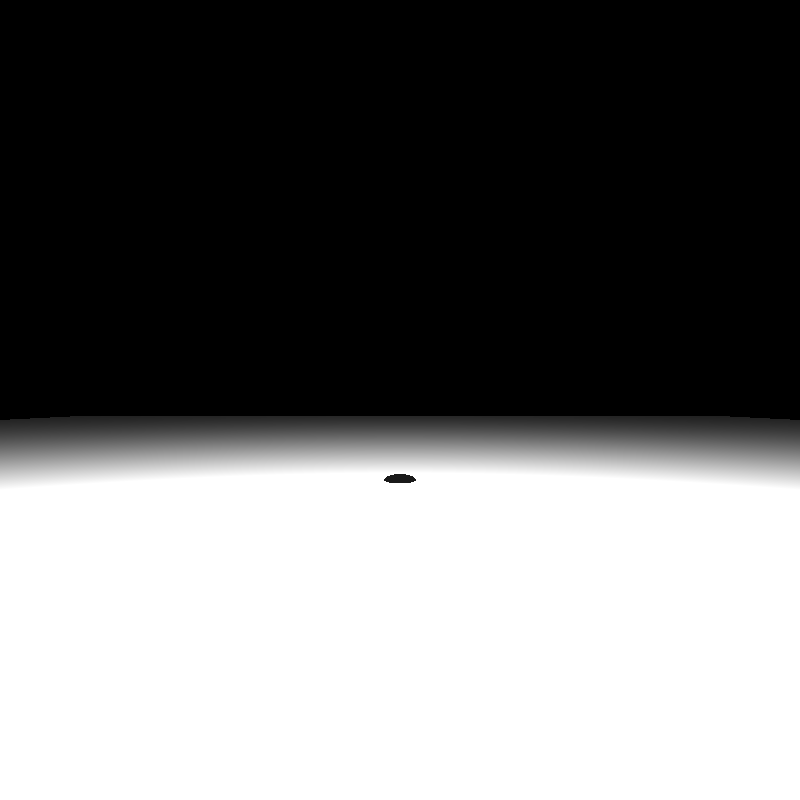

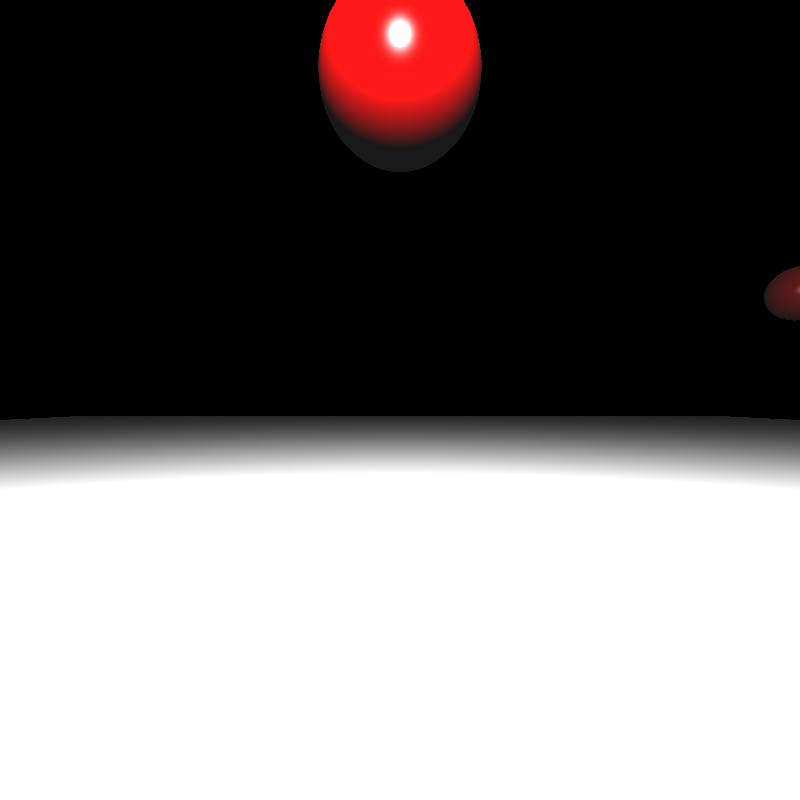

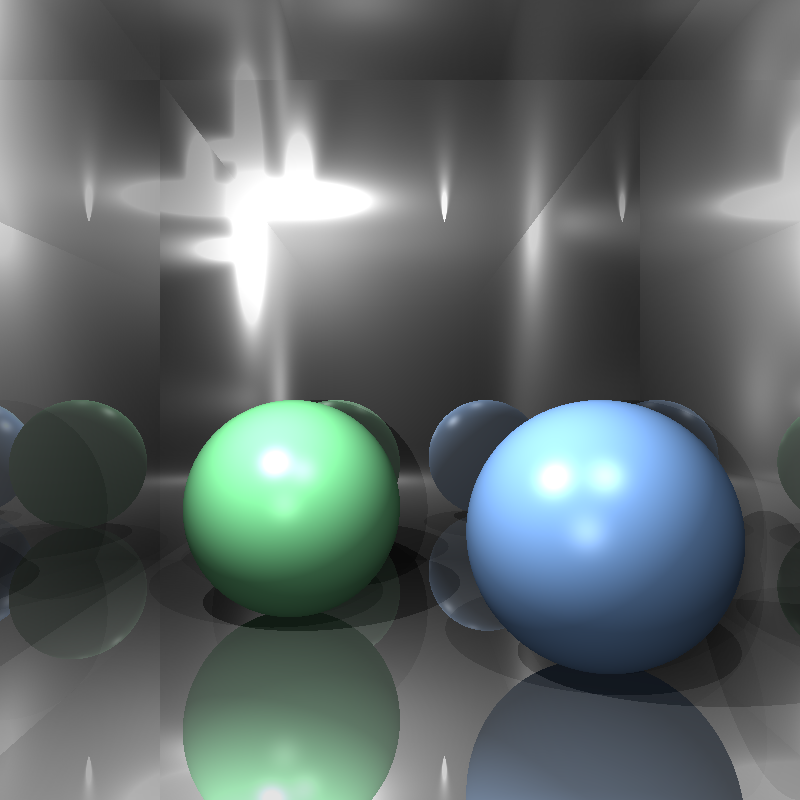

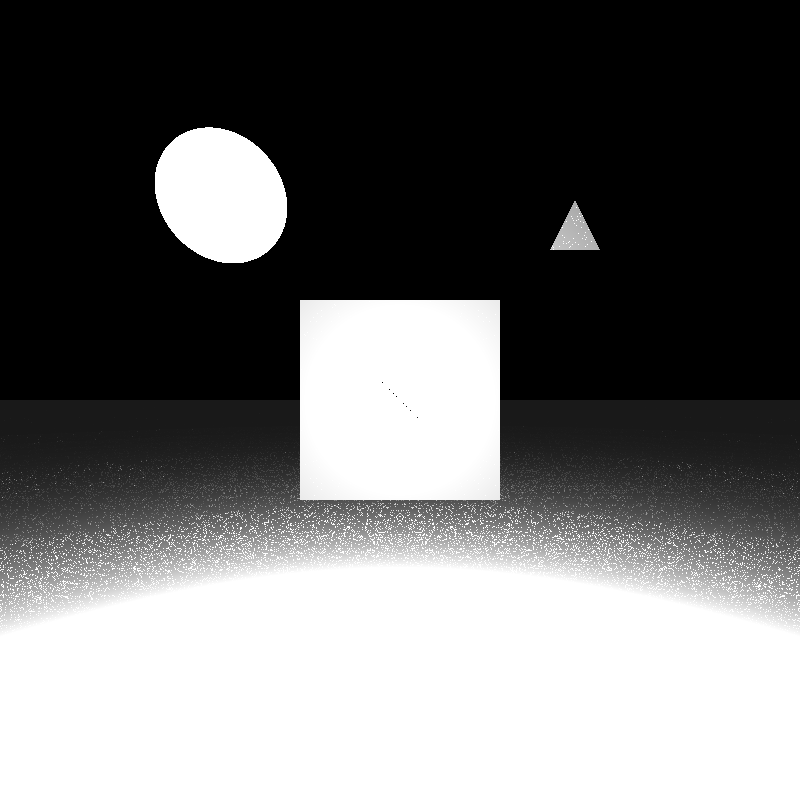

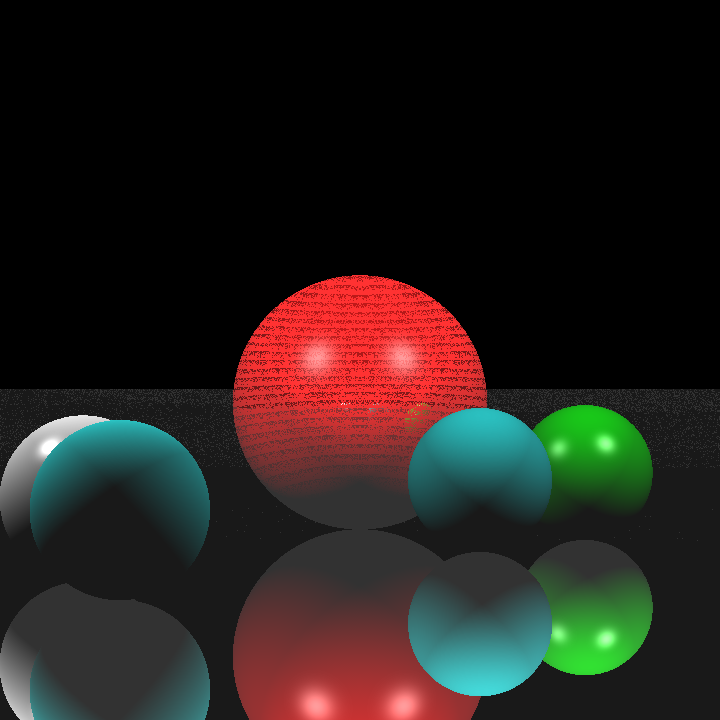

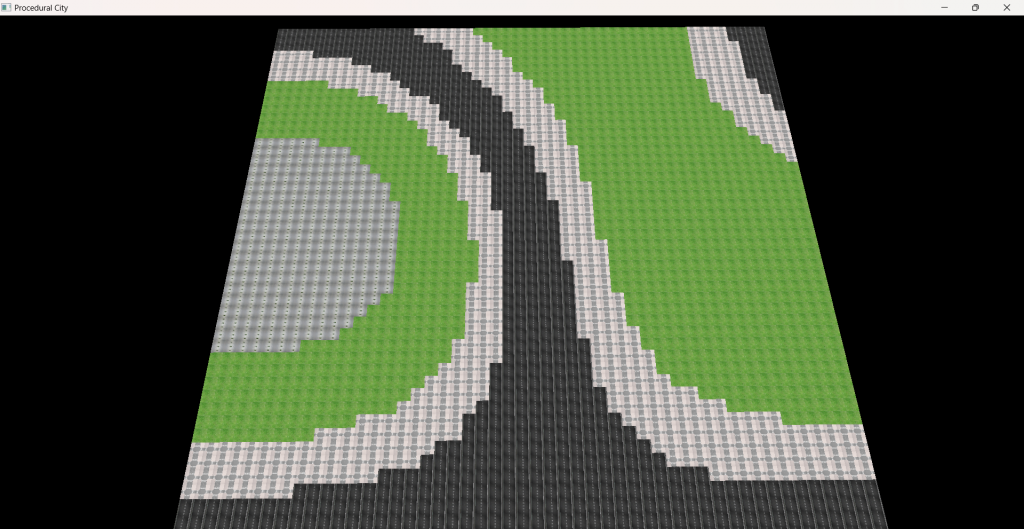

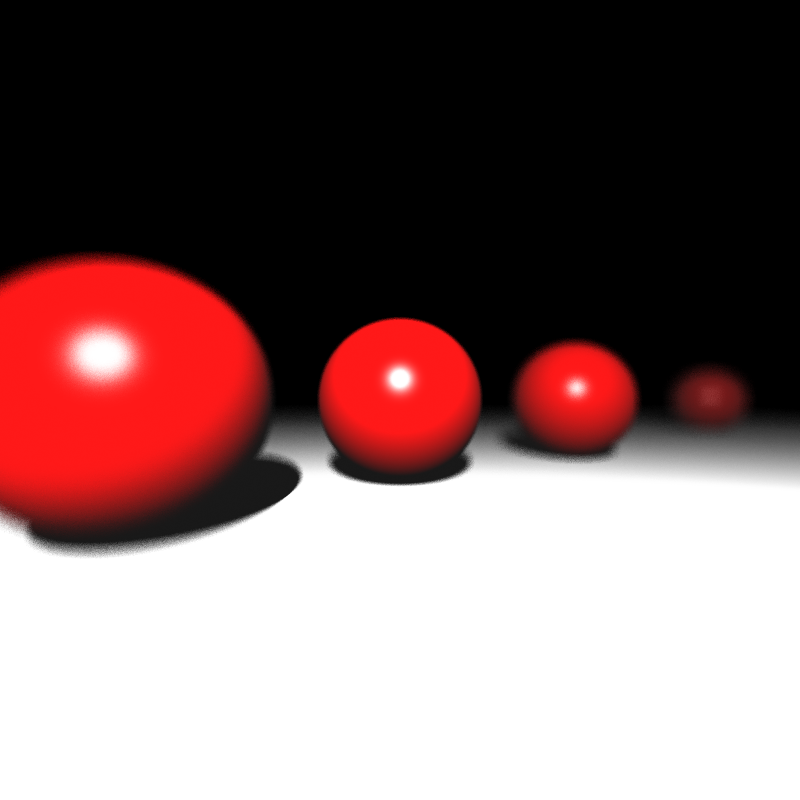

Next in the list was depth of field. After implementing area light, I learned my lesson to normalize the random values when necessary, so I didn’t encounter any problems there. Instead I miscalculated the size of the horizontal and vertical step to find the random aperture sample point. I accidentaly used the image plane width and height instead of pixel width and height which gave the result below when rendering spheres_dof.json:

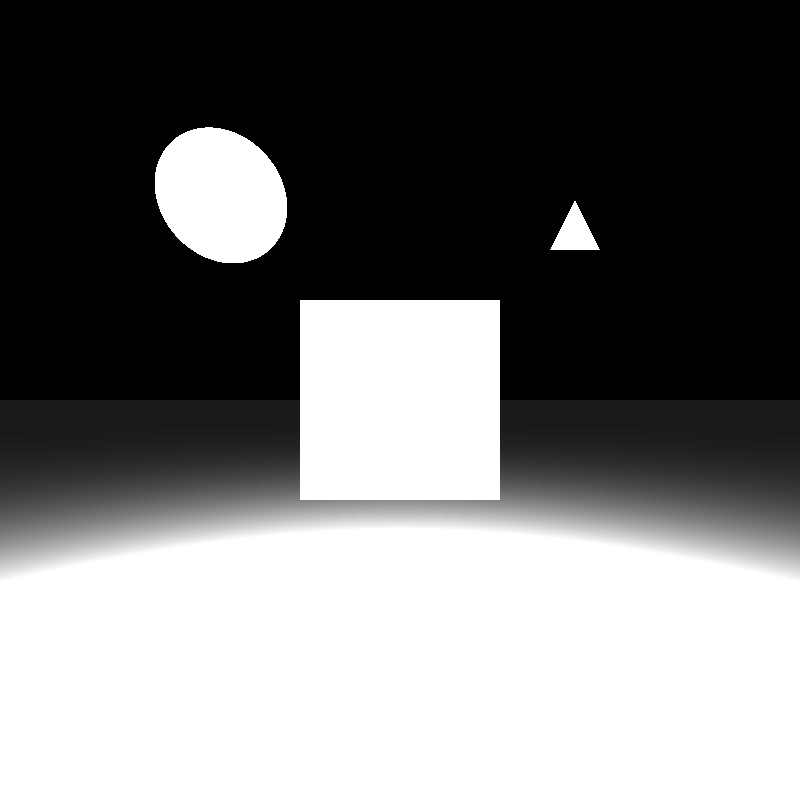

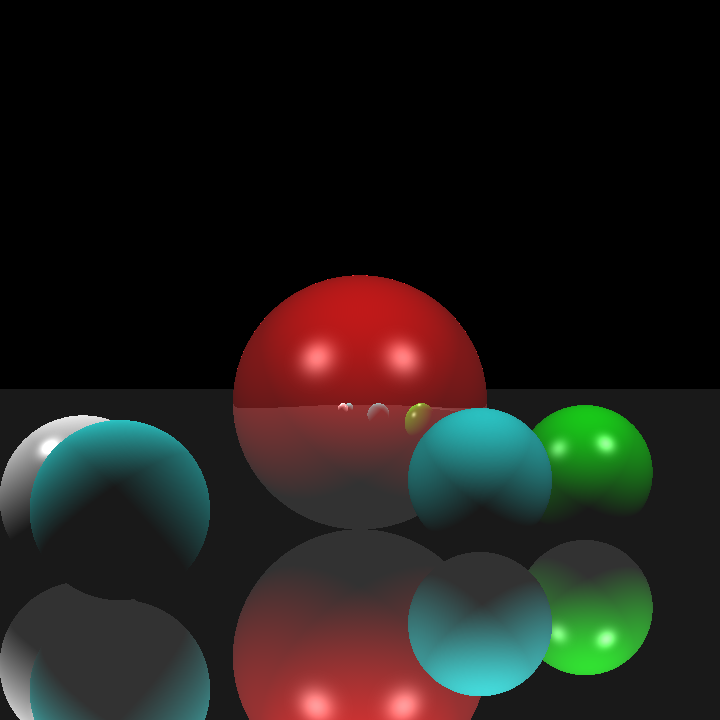

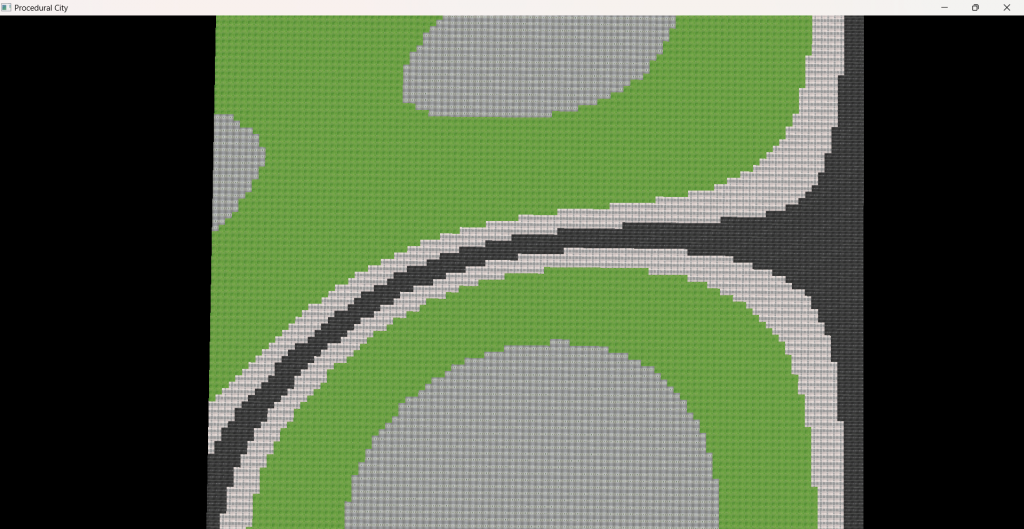

After fixing this minor issue, I got the correct result:

Motion Blur

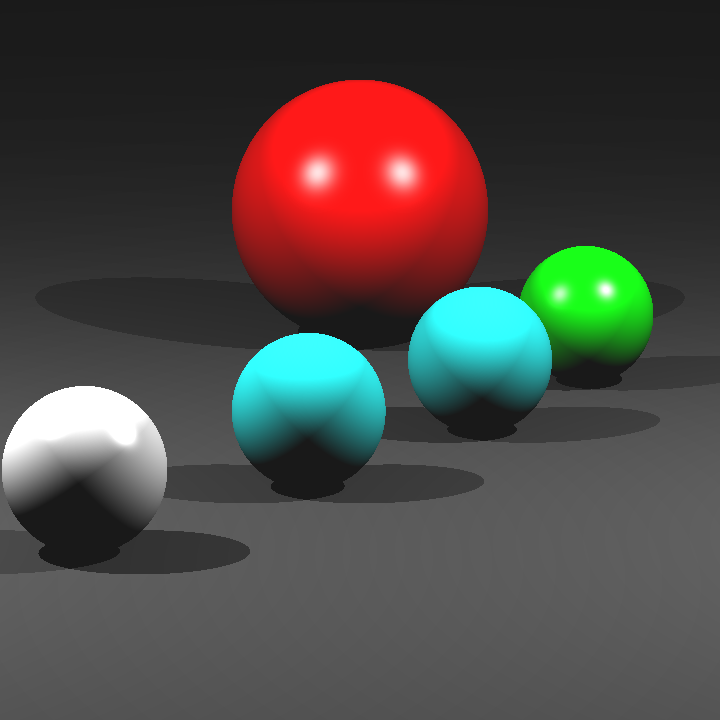

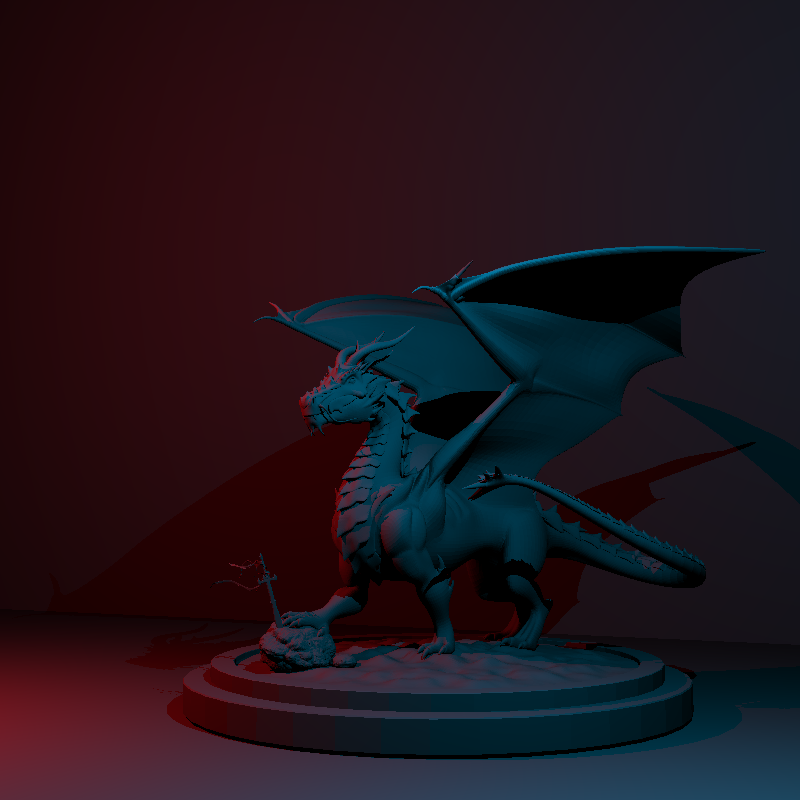

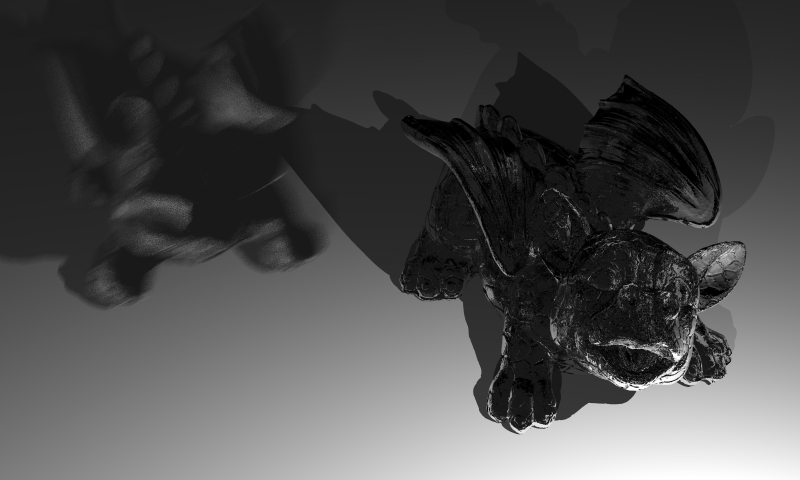

Implementing motion blur was a bit trickier than the previous features as I had to modify my BVH implementation a bit to accomodate objects with motion blur. For those objects, I recalculated their bounding box from both their vertices at t = 0 and t = 1, which gave me the largest extent that included every possible positioning of that object. To calculate intersection with objects that had motion blur, I translated the ray origin in the opposite direction instead of transforming the entire geometry. This implementation gave the result below for dragon_dynamic.json:

I’m not quite sure why the colors are off, but I didn’t have much time to try to figure out the reason behind it, so I moved on to glossy reflections.

Glossy Reflections

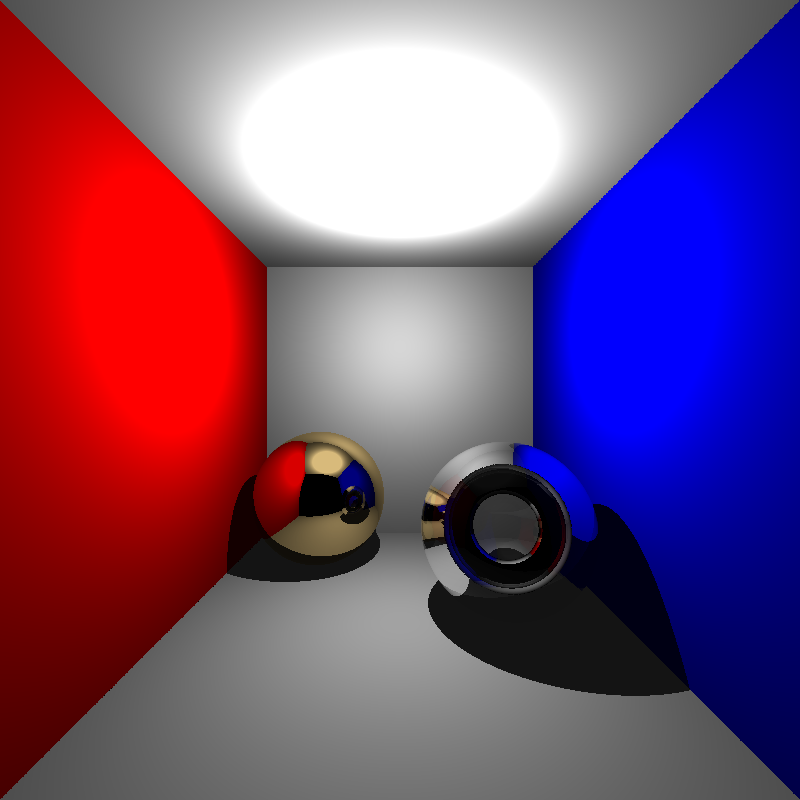

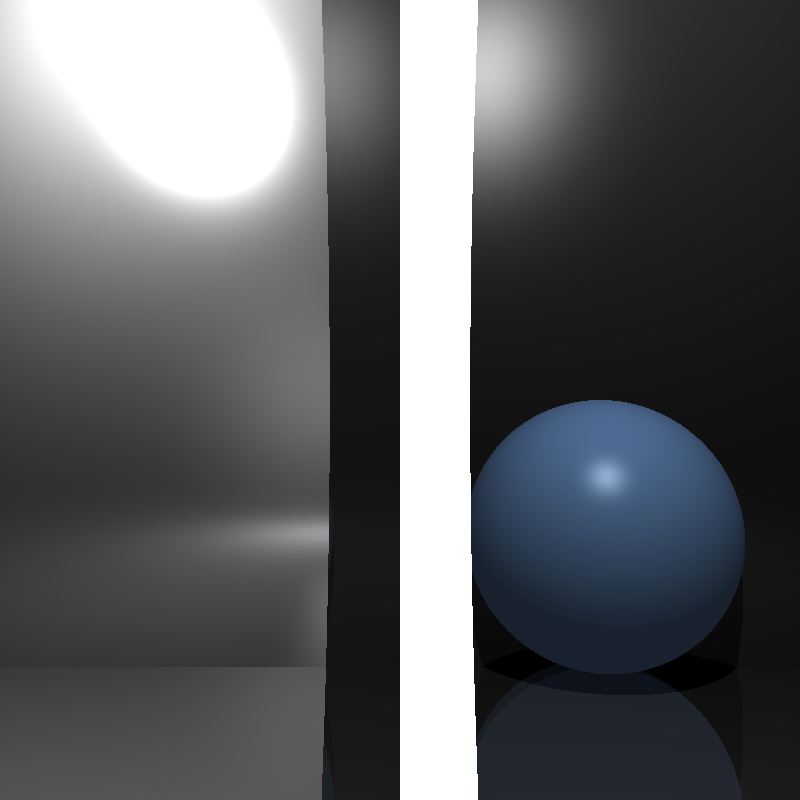

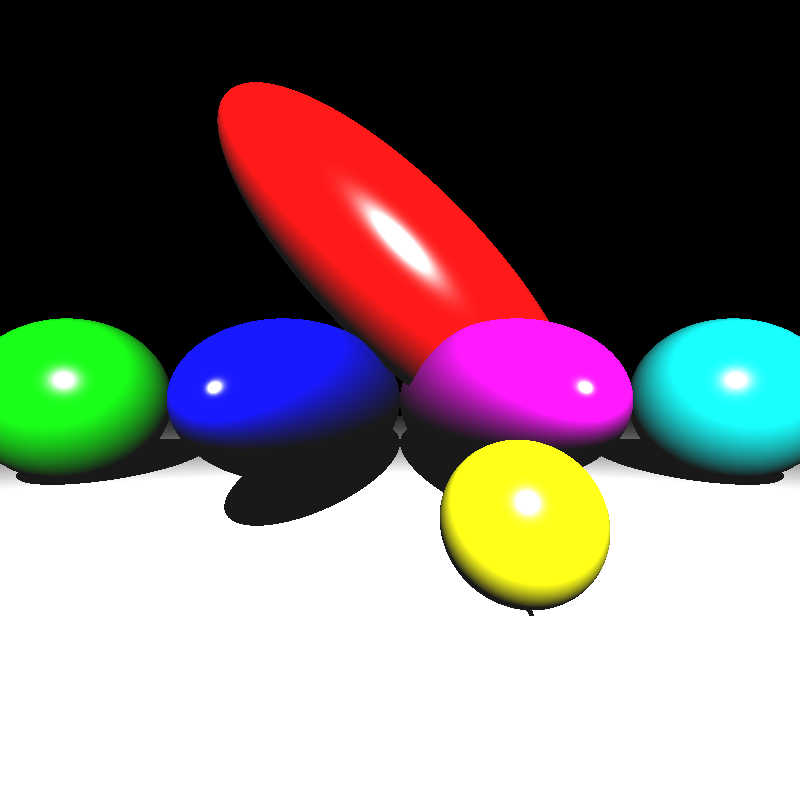

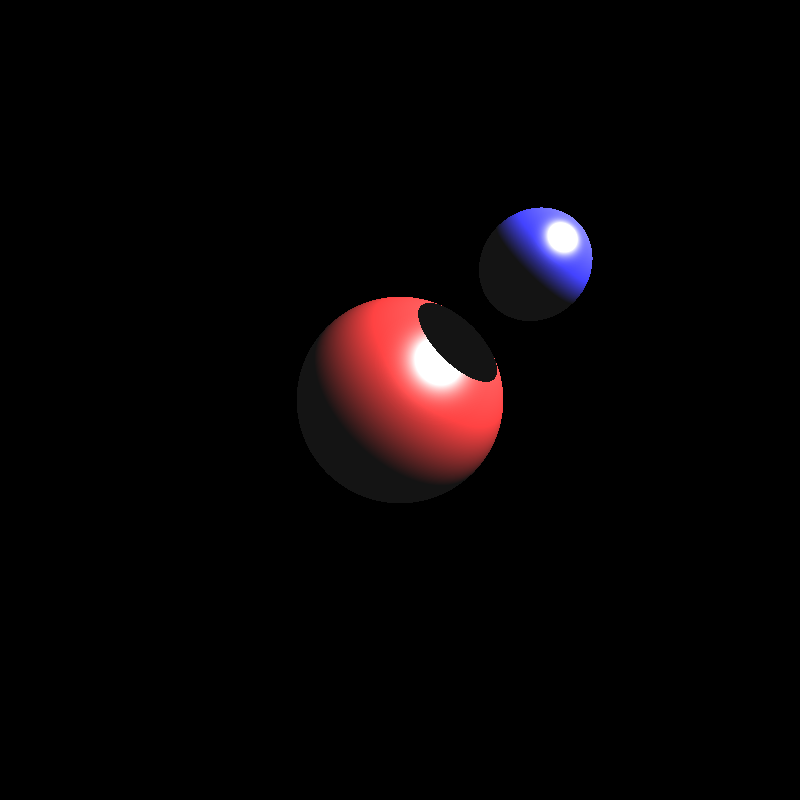

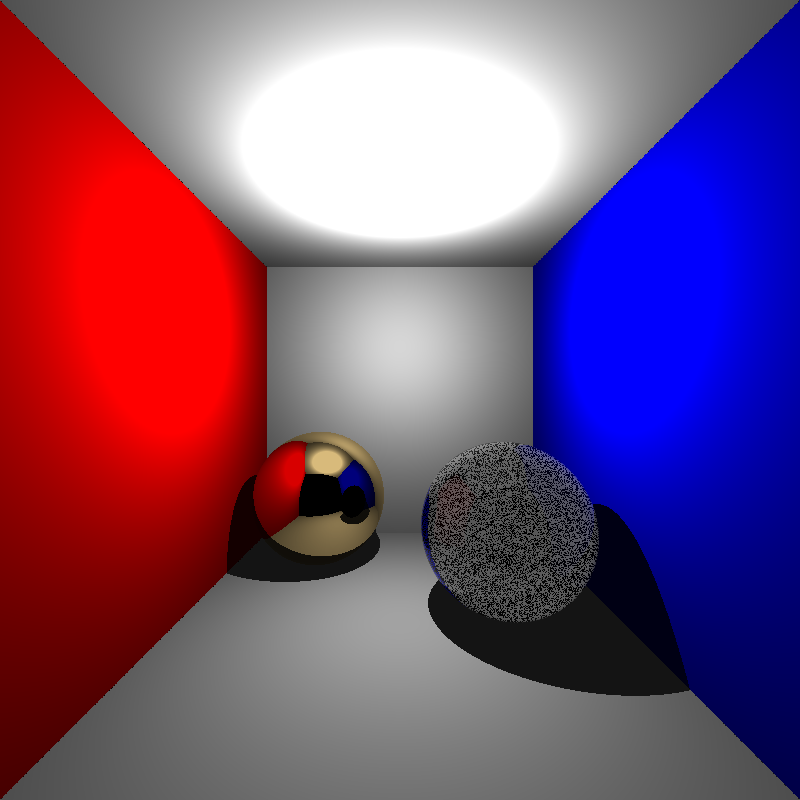

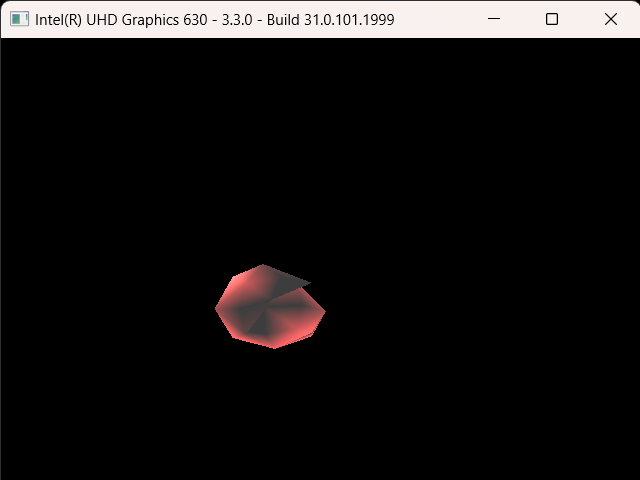

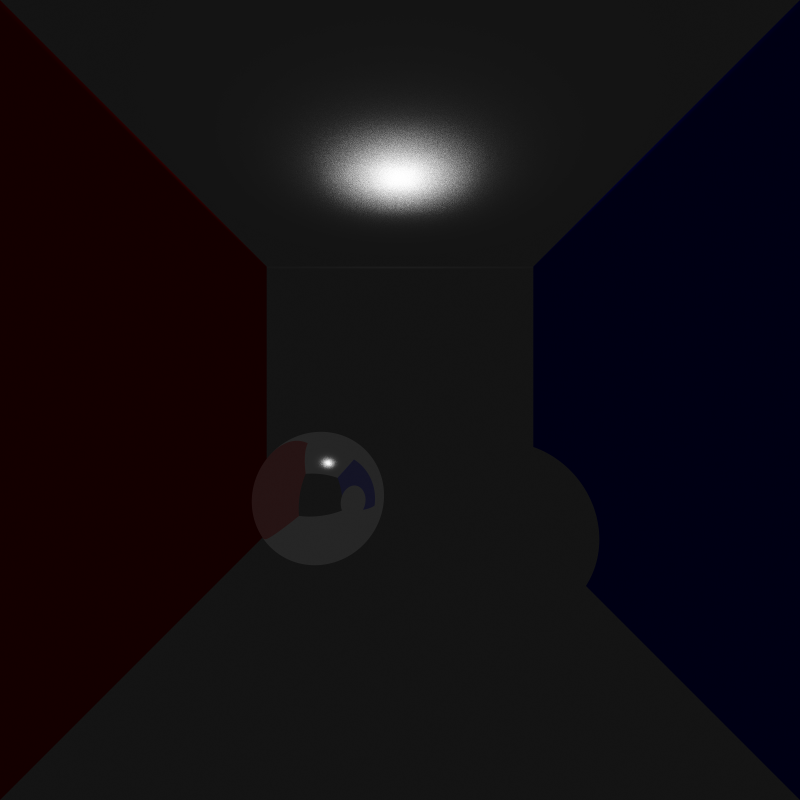

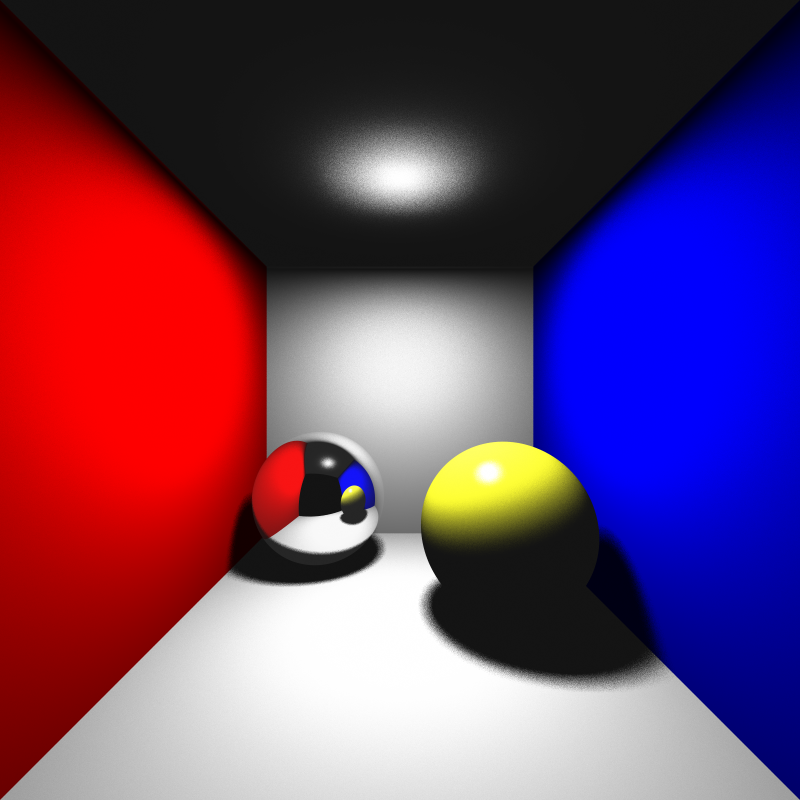

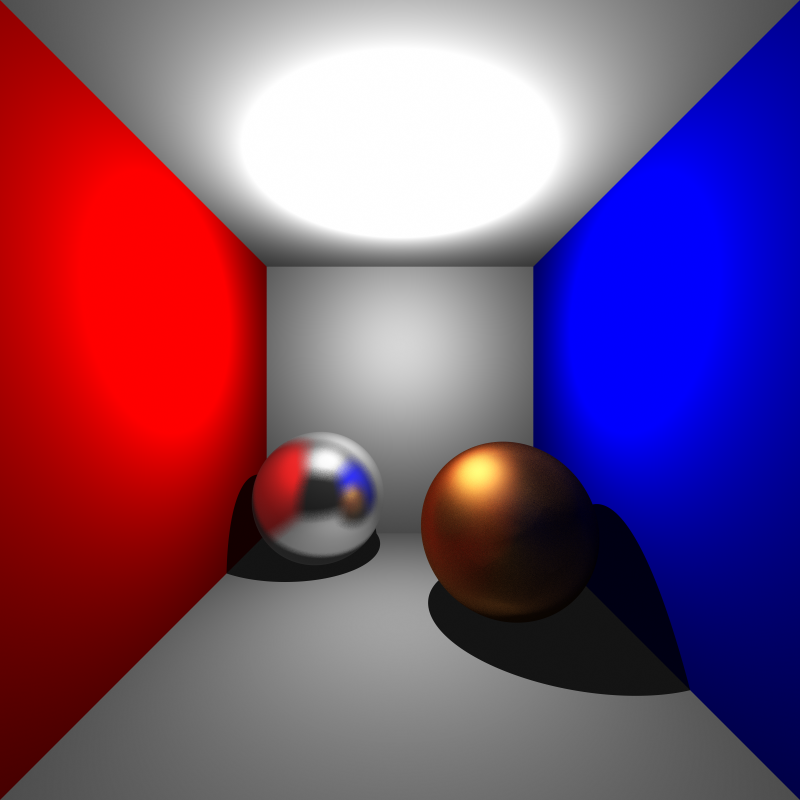

When implementing glossy reflections, I wasn’t quite sure how I should apply the given roughness value, so I decided to simply multiply the offsets by the roughness value itself. Perhaps more interesting results could have been obtained with various roughness functions, but I didn’t want to spend too much time on it, at this point I had an hour or two until the deadline. I calculated the offsets with two random values and obtained the result below for cornellbox_brushed_metal.json:

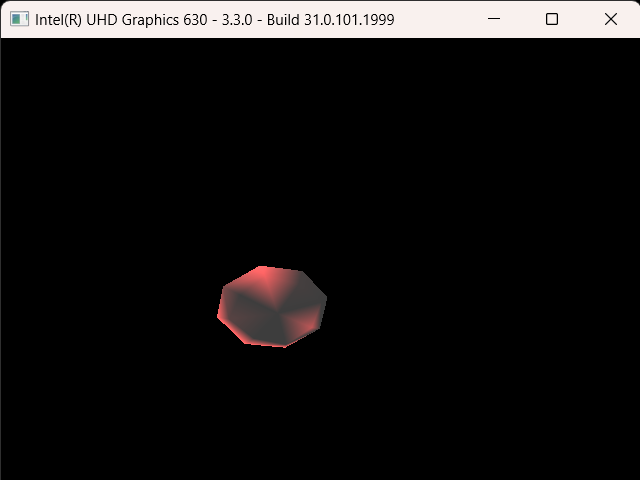

Turns out I hadn’t actually learned my lesson after implementing area lights. I had yet again forgotten to normalize the random values. After normalizing them I got the result below:

Remaining Issues and Render Times

During this blog post I didn’t mention some scenes relevant to the topics I was discussing. That’s because some scenes are rendered completely black for some reason and I have no idea why. While cornellbox_area, cornellbox_brushed_metal, and dragon_dynamic are being rendered just fine, cornellbox_boxes_dynamic and focusing_dragons result in a completely black image. Similarly chessboard_arealight is rendered fine while renderings of chessboard_arealight_dof and chessboard_arealight_dof_glass_queen result in an almost completely dark image with a small patch that is slightly brighter. Unfortunately, I didn’t have time to figure out the reason behind these issues, so hopefully I’ll figure it out while implementing the next homework. Below are some extra scenes and the render times of scenes that produced proper results:

| Scene File | Render Time (seconds) |

| spheres_dof.json | 27 |

| cornellbox_area.json | 49 |

| cornellbox_brushed_metal.json | 190 |

| chessboard_arealight.json | 74 |

| metal_glass_plates.json | 222 |

| wine_glass | 6213 |

| dragon_dynamic.json | 27925 |