For the second homework of my CENG 795: Advanced Ray Tracing course, I tried to expand my previous ray tracer by adding its missing features from the previous homework, adding an acceleration structure (specifically a BVH with median split method), and modifying the parsing and tracing to support mesh instances and transformations. Most of these attempts failed unfortunately. Nevertheless, I will be explaining every step of my implementation and providing some rendered images from my attempts below.

Wrapping the Tracing Process and Re-attempt at Refraction

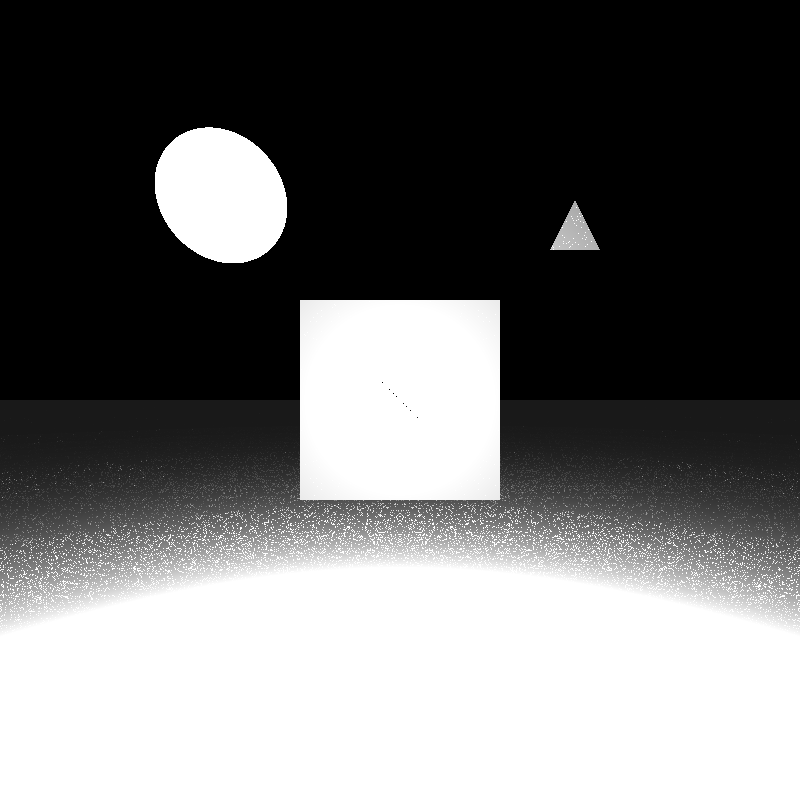

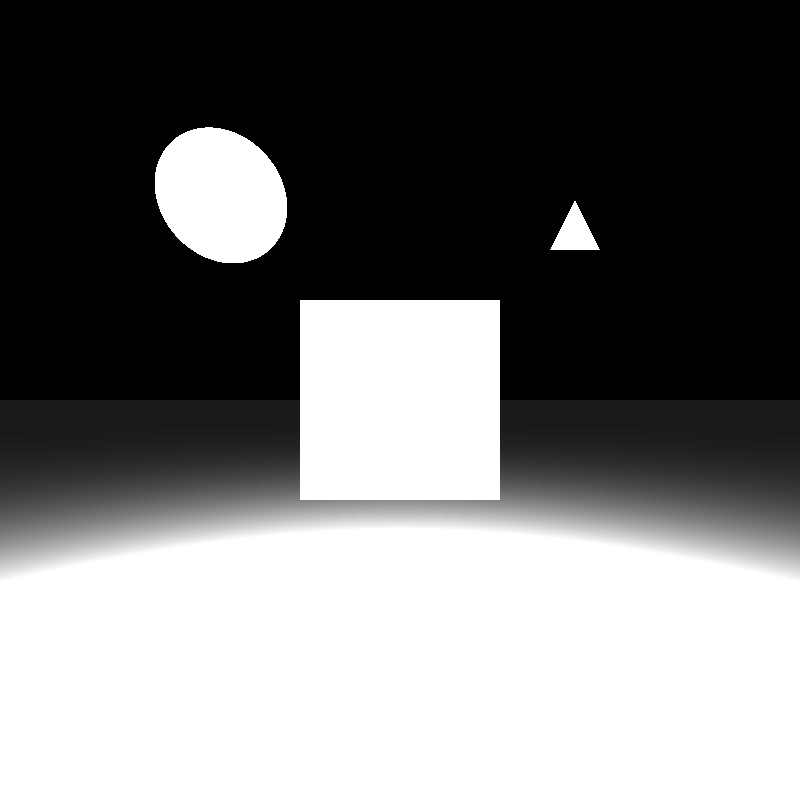

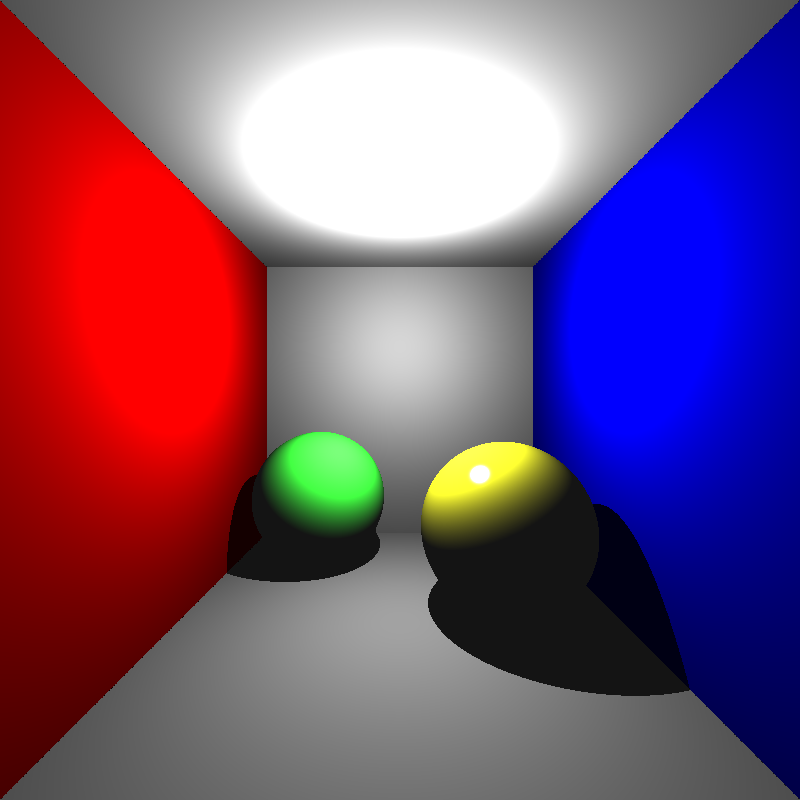

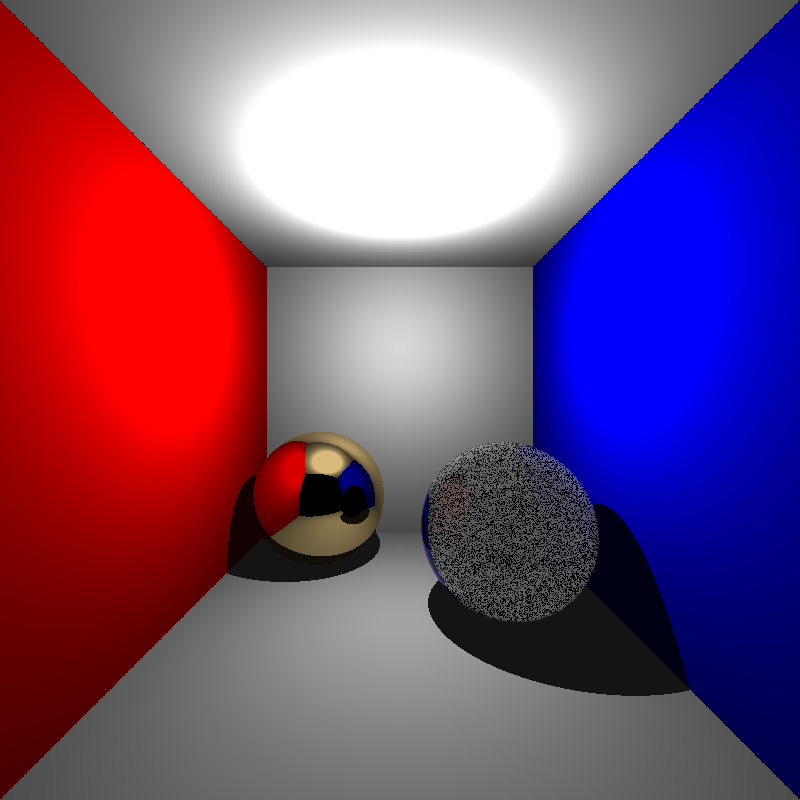

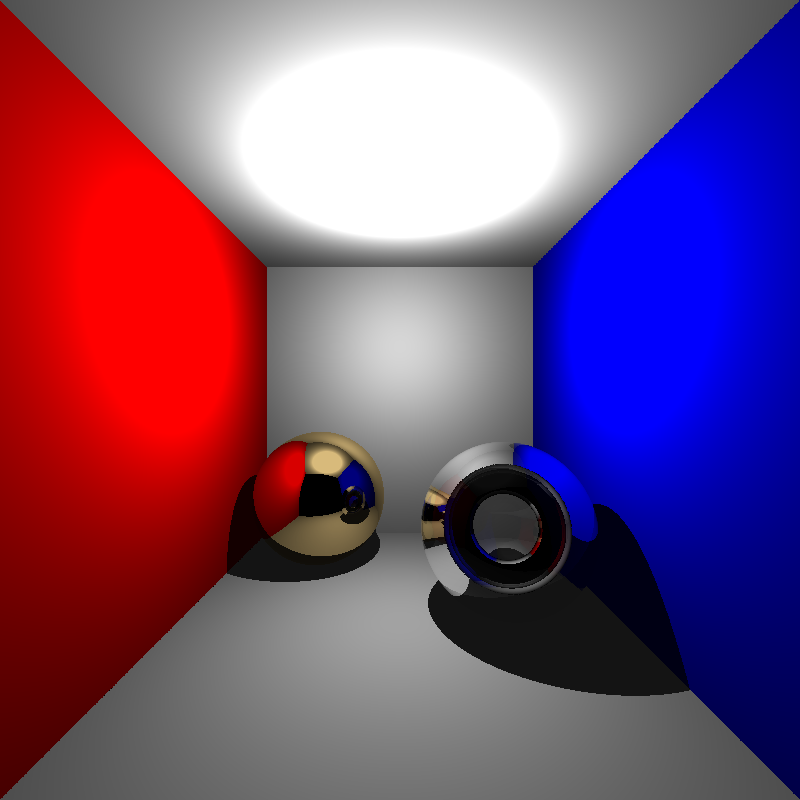

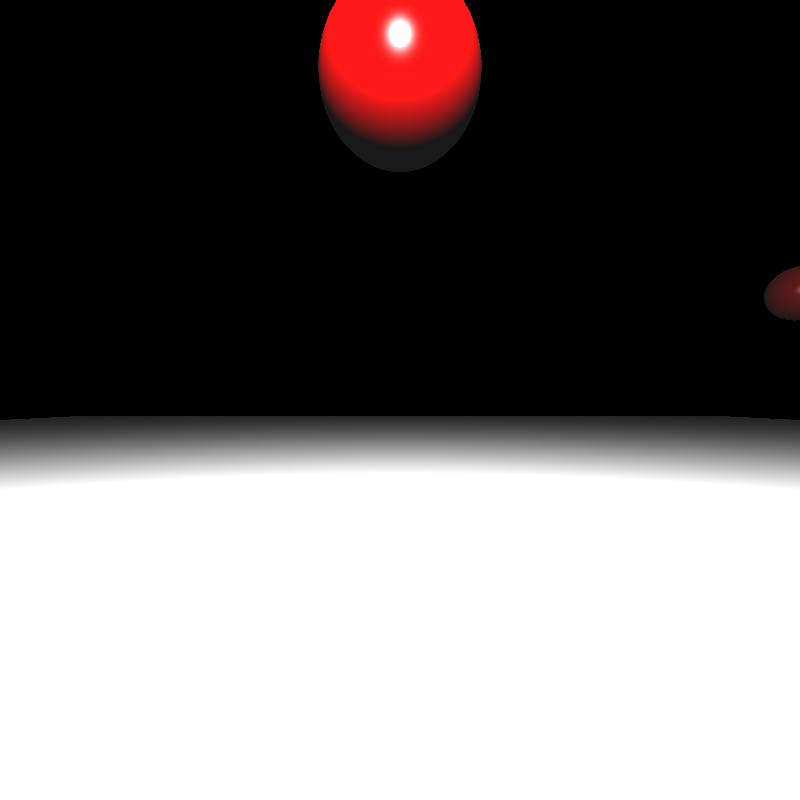

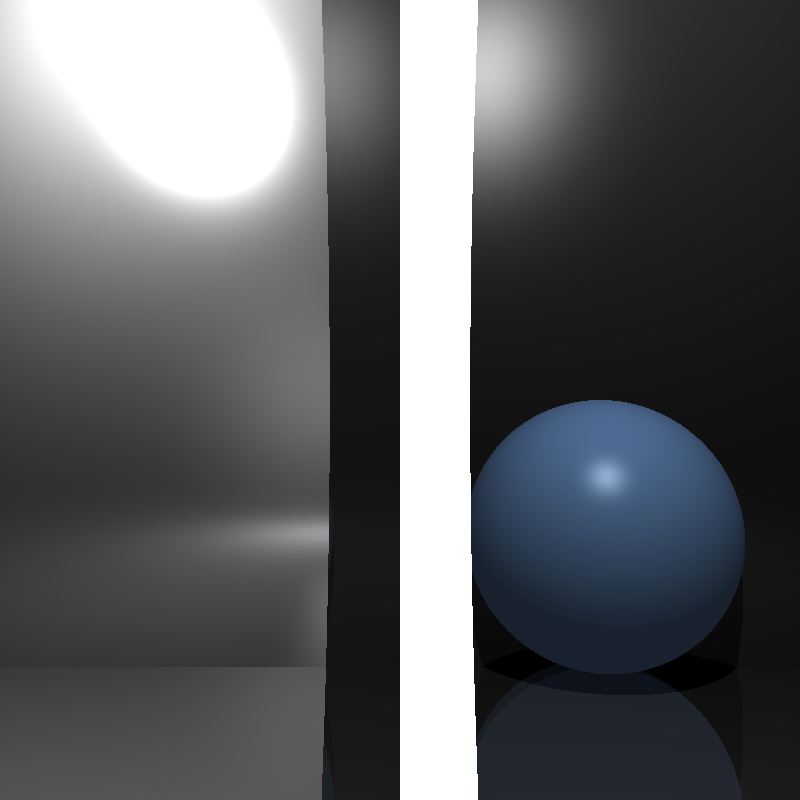

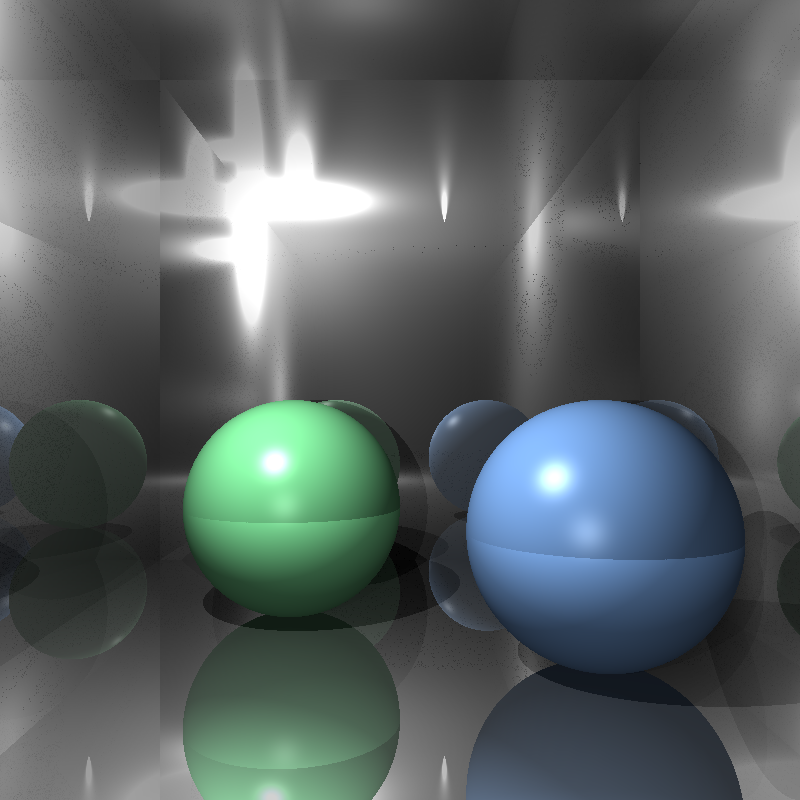

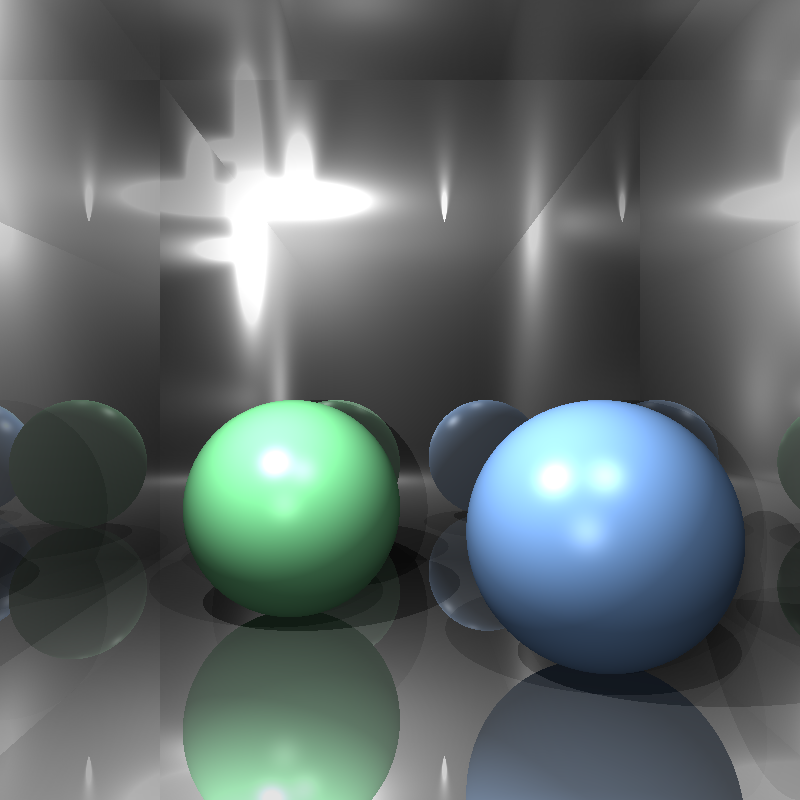

Before I began implementing the required features of this homework, I believed that I needed to move my tracing functions into a single trace function so that calculating hit detection during BVH traversal would be easier and I could perhaps fix my refraction calculation during this process. I wrapped the tracing process in a single function called trace() that recursively calls for itself when it detects reflection or refraction. The calculations for intersection, color, shadow, and reflection are essentially the same before, but I rewrote my refraction calculation. My refraction calculation now supported multiple reflection and refraction iterations instead of one, and the reflection and refraction weights are clamped in case one of them exceeded 1. The images below are renderings of cornellbox_recursive.json; the top image is rendered by my previous ray tracer, and the bottom image is rendered by my modified ray tracer:

While the dielectric sphere is rendered a lot better (at least parts of the background are visible now) the refractions were still very off. This result was still not quite acceptable, but I did not want to waste too much time on details that were irrelevant to this homework, so I moved on with my implementation.

Applying Transformations

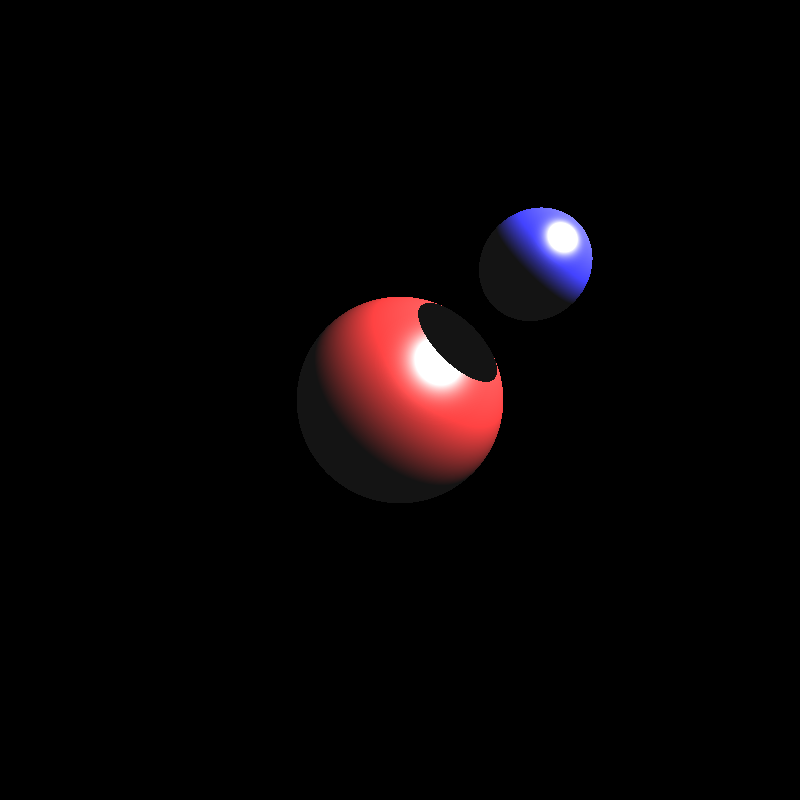

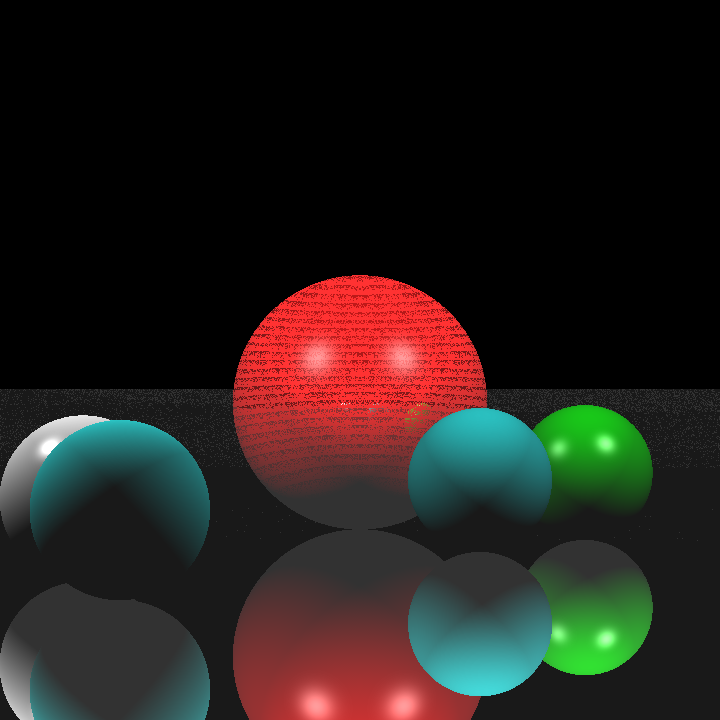

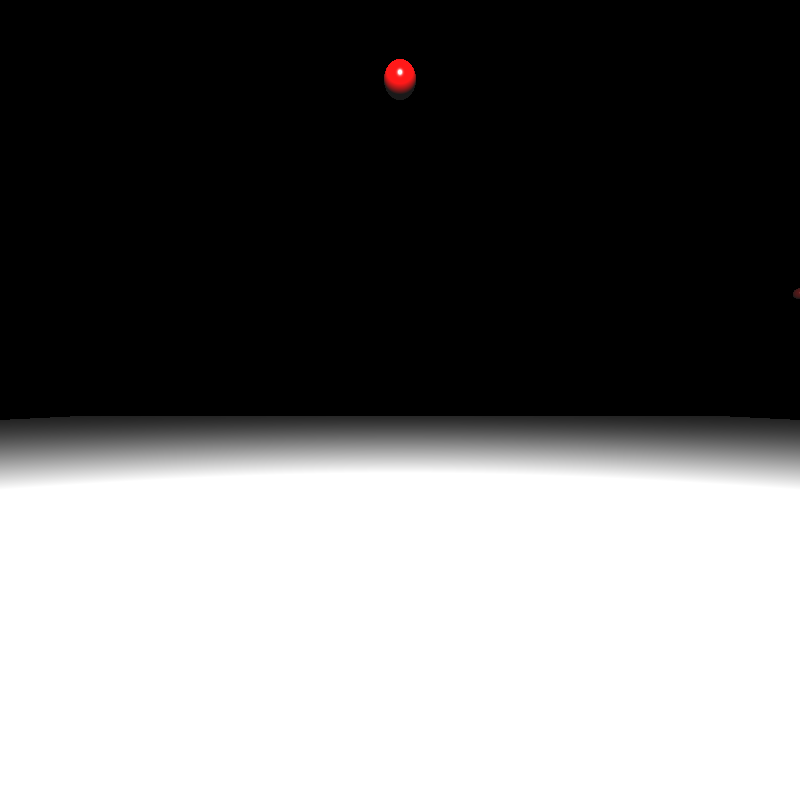

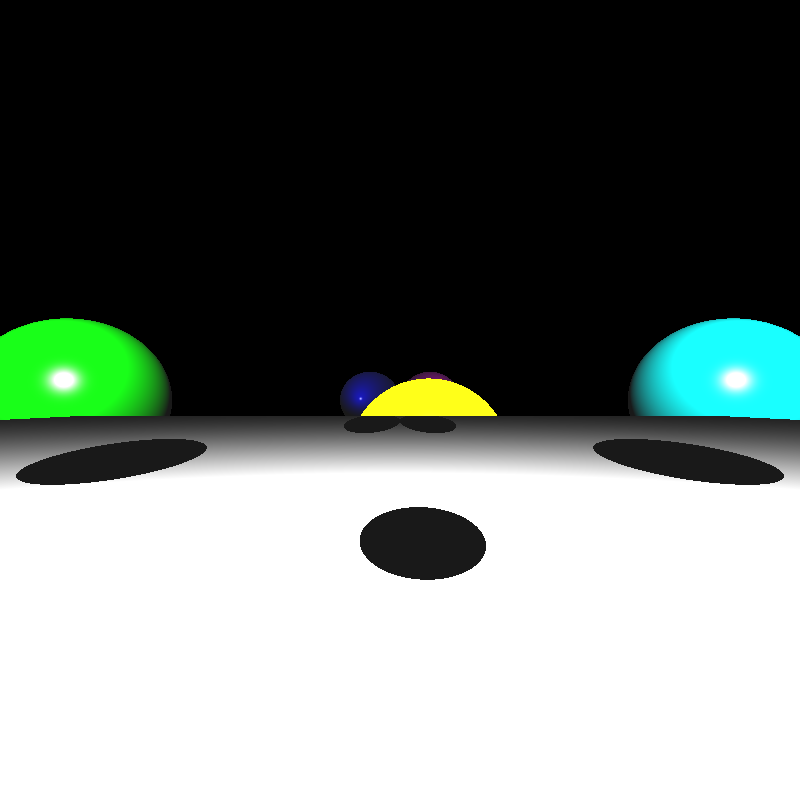

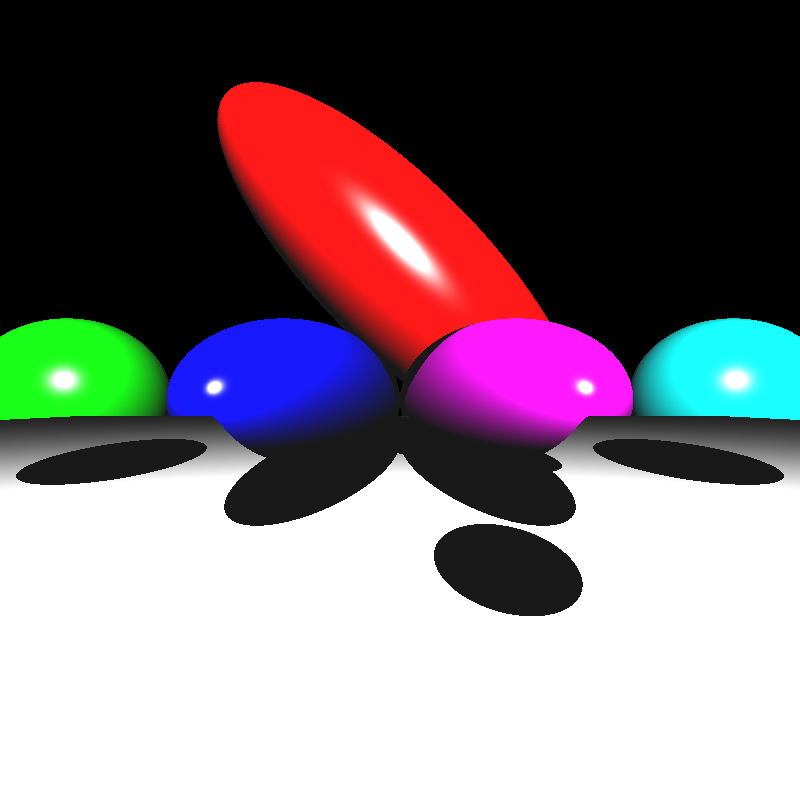

To apply transformations to objects, I decided to store the composite transformations for the object vertices and their inverse transposes for their normals initially. Then I would apply the transformations on each vertex and normal before rendering and calculate intersections through world space. After spending a little time implementing and fixing some minor bugs, this implementation seemed to have worked, at least for simple scenes. But I noticed a problem for spheres that had non-uniform scaling transformations. Below is a rendering of spheres.json when I tried to apply the transformations to the objects:

This result was quite perplexing. The process of calculating the composite transformations and applying them should have been incredibly simple. After going over my implementation, I couldn’t really find any problems either (But there actually was a major problem that I overlooked, much to my dismay. I’ll talk about the problem toward the end of this section). Then I realised something. The radii of the spheres never got transformed. As no multiplication operations could be done on them, the radii would not change and the spheres would still appear as uniform spheres instead of ellipsoids. While I could have multiplied the radius by the common diagonal value for uniform scalings, this would not have worked for non-uniform scalings.

While searching the internet over this issue, I found these posts that had interesting ideas:

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/34220370/apply-matrix-transformation-to-a-sphere

https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/3159618/principal-axes-of-deformed-ellipsoid

Transforming the sphere into an ellipsoid with different principal axes sounded interesting, but it felt like trying to implement something like this would have put too much unnecessary work, so I decided to apply the inverse of the transformation on the ray position and direction for each object and calculate that way.

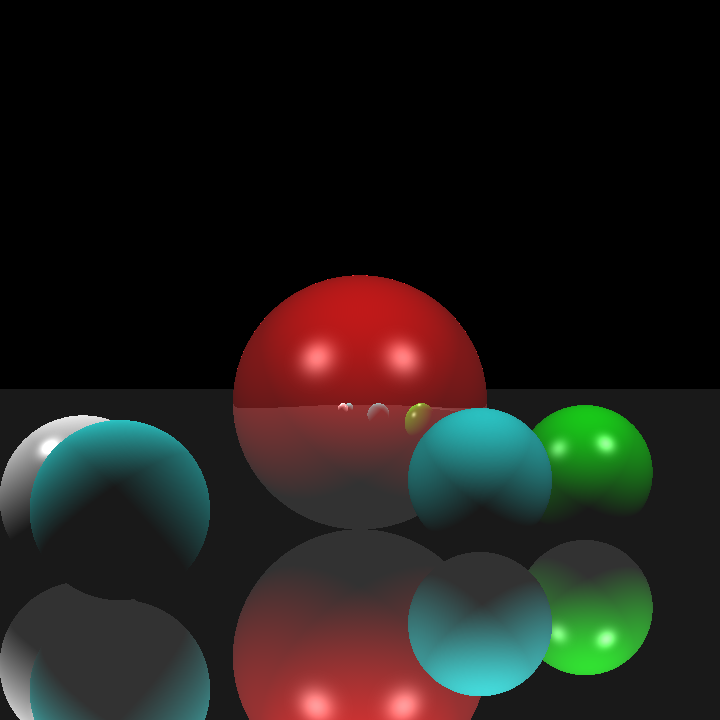

When I finished implementing it, I got the results below:

The reason for this was incorrect intersection calculation, which was caused by several minor mistakes like using local t values to compare instead of t values for world space and setting the w component of directions (such as ray direction and normal) to 1 instead of 0. Fixing these issues still gave me incorrect results:

Still oddly incorrect results yet I was sure there were no errors in my implementation. After spending a considerable amount of time contemplating over this, I finally found the major problem I mentioned before. The problem was in the order of matrix multiplication. When calculating the composite transformations I put the matrices in incorrect order. The amount of small yet crucial details I managed to overlook is honestly astonishing. I doubt anyone could match me when it comes to that.

With the transformation ordering now fixed, I got the results below:

Somehow the results were still incorrect, but I had had my fill of transformations at this point, so I decided to move onto implementing the BVH.

Implementing BVH, Mesh Instances, and PLY Parsing

I normally intended to explain mesh instances and ply parsing in another section, but I could not implement them in time, so I decided to explain them in this section. This entire section is actually more about my shortcomings as even my BVH implementation seems to be almost useless.

For my BVH implementation I tried to implement a two-level, linear BVH tree with median splitting where each mesh would have its own bottom level BVH tree. For this, I wrote a small bounding box struct that just held the minimum corner, maximum corner, and its center. I then wrote a primitive struct that would represent each object and stored these primitives in the array. Each BVH node would keep track of its primitives by primIndex and primCount. In the BVH tree itself, each node’s left child is in the next index of the parent and the right child is offset by rightOffset. Below is a simplified version of these structs:

struct BBox {

parser::Vec3f min_corner; // minimum x, y, z of the box

parser::Vec3f max_corner; // maximum x, y, z of the box

parser::Vec3f center;

BBox() {

min_corner = {0.0, 0.0, 0.0};

max_corner = {0.0, 0.0, 0.0};

center ={0.0, 0.0, 0.0};

}

BBox(parser::Vec3f min_vec, parser::Vec3f max_vec, parser::Vec3f center_vec) {

min_corner = min_vec;

max_corner = max_vec;

center = center_vec;

}

};struct BVHNode {

BBox bbox;

uint32_t firstPrim; // index in primitives[]

uint16_t primCount; // leaf count

uint16_t rightOffset; // index offset to right child

uint8_t nodeType; // 0=leaf, 1=interior

};struct Primitive {

BBox bbox;

enum { SPHERE, TRIANGLE, MESH_TRI, MESH_TOP } type;

parser::Sphere sphere;

parser::Triangle tri;

parser::Mesh mesh; // only valid for MESH_TOP

std::vector<Primitive> meshFaces; // for per-mesh BVH

std::vector<BVHNode> meshBVH;

parser::Matrix4f inverse_transform;

Primitive(parser::Sphere s);

Primitive(parser::Triangle t);

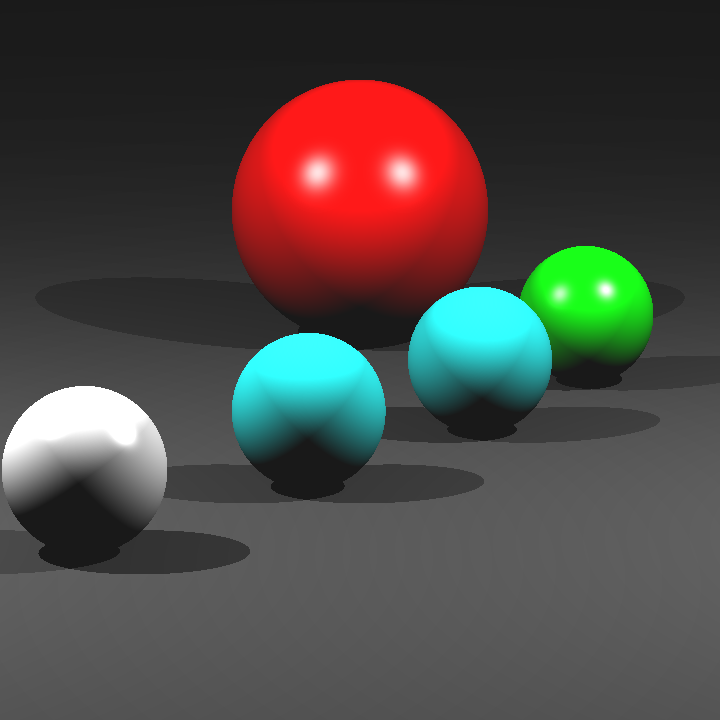

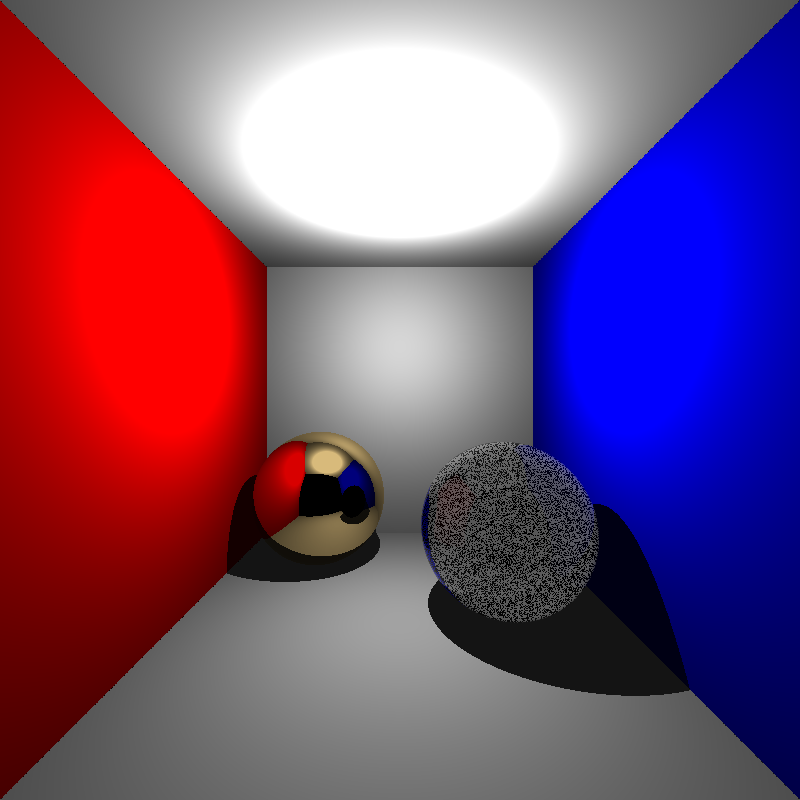

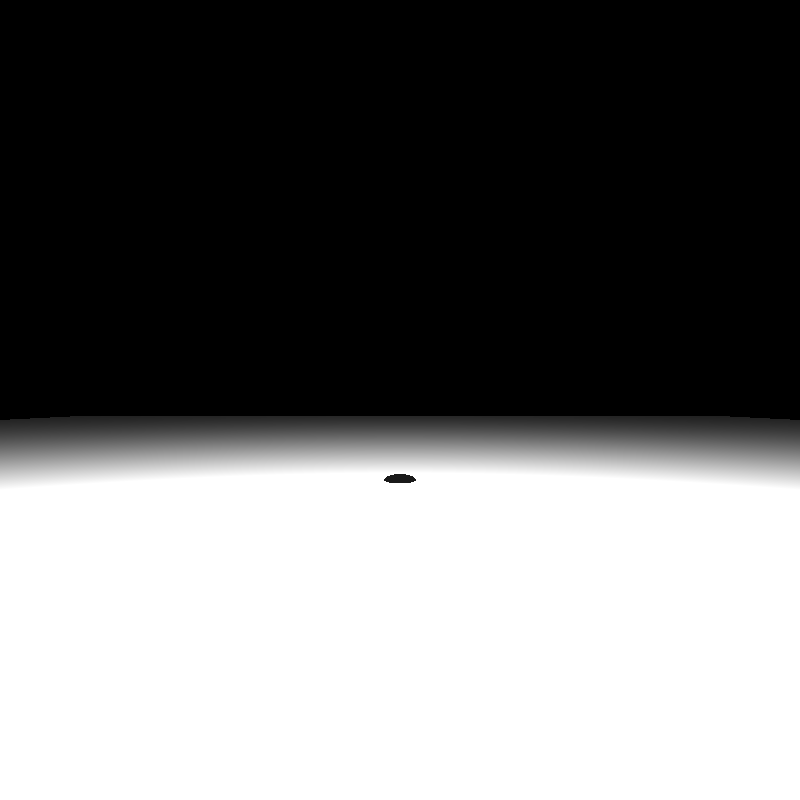

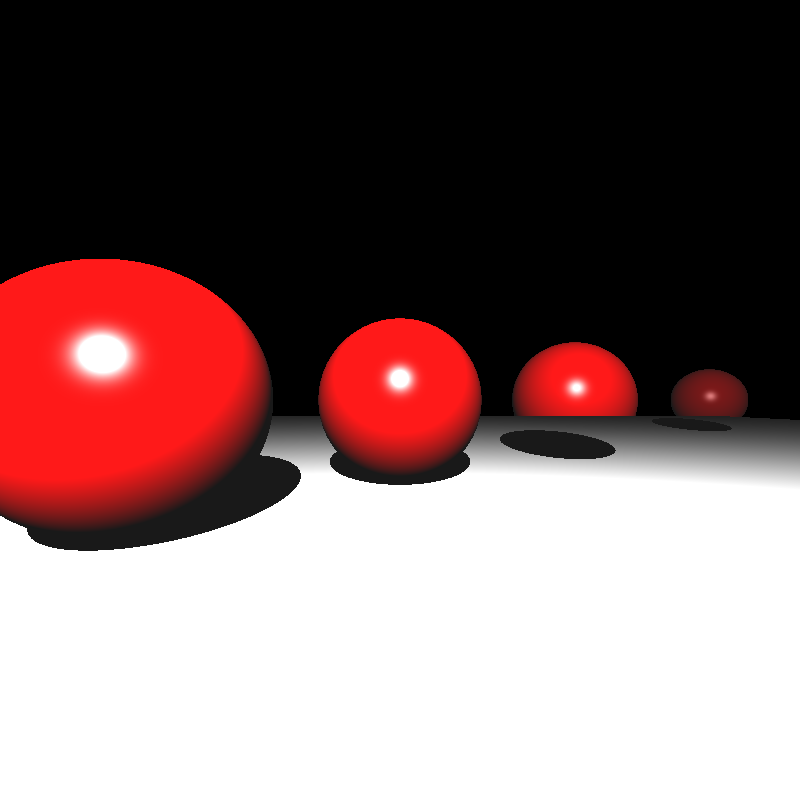

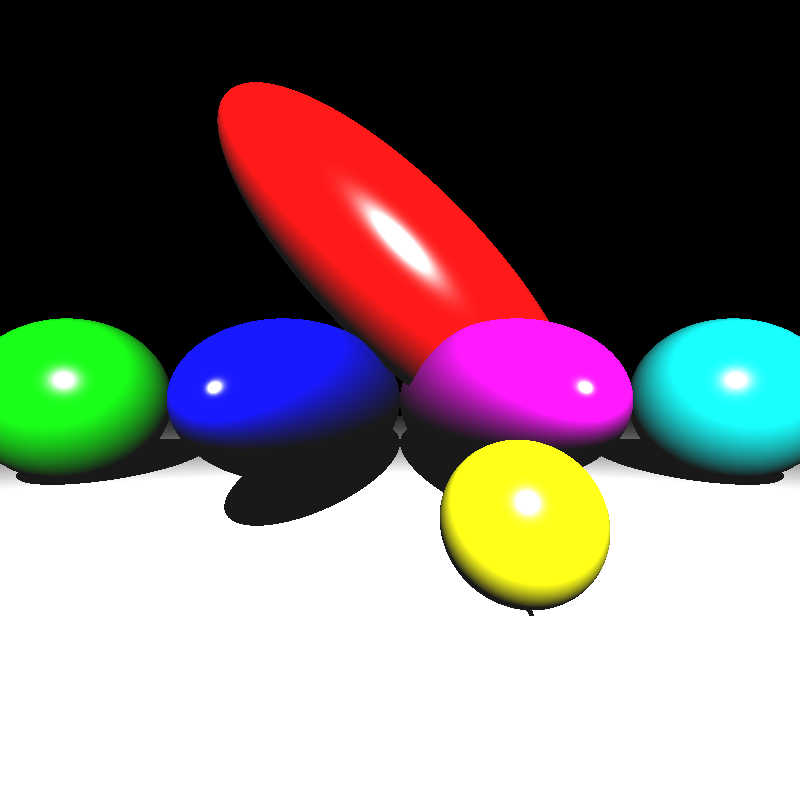

Primitive(parser::Mesh m);

};My structs probably could have been more efficient, but my initial priority was to get a working BVH. I built a BVH recursively and assigned primitives to each split by which side they are on compared to the median of the given bounding box. When I ran my ray tracer on some simple scenes, I got the results below:

Oddly enough, these scenes were now being rendered properly. I couldn’t figure out the reason behind this, but probably there was still something wrong with my intersection calculation.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t implement a parser for PLY files. I tried to use the ply library by Paul Bourke, but I could not get it to work no matter what I did. I also tried to get Google Gemini to produce a parser for me (it was the only model working when Cloudflare was down), but its implementation didn’t work either. For mesh instances, the ones in the example files all referenced PLY meshes as their base meshes, so I couldn’t really get around to implementing that. It felt like it would be pointless if the base meshes did not exist. I didn’t give a table for render time either because the simple scenes that could be rendered take a second at most and I don’t have render times for complex scenes that use PLY files.

In the end, this homework turned out to be less about producing a flawless ray tracer and more about discovering just how many ways I can break one. I was quite impressed by the amount of mistakes I’ve made. In any case, I’ve come to understand the importance of writing modular and maintainable code that can be extended as needed for future use.